Rent seeking is the type of behavior GekeVenns seek to expose: the act of tapping into government funds. Auburn University's Glossary of Political Economy Terms defines it this way: “all of the various ways by which individuals or groups lobby government for taxing, spending and regulatory policies that confer financial benefits or other special advantages upon them at the expense of the taxpayers or of consumers or of other groups or individuals with which the beneficiaries may be in economic competition.”

The concept originated in 1967 with Gordon Tullock, the father of public-choice economic theory, but it was Anne Krueger in 1974 who coined the term, “rent seeking.” And it's the type of behavior people mean when they criticize a company for only caring about profits. Of course, all companies care about profits, even the most enlightened and sincere companies. If they didn't, they'd fail. But when we typically fault a company's actions in this way, it's not for profit-seeking, but for rent-seeking. Economics professor Sandy Ikeda at fee.org explains the difference:

If the rules say that the acceptable way to improve your situation is to provide a product or service that consumers would be willing to pay more for than the opportunity cost of the resources used, then that’s what you’ll tend to do. In that case, if you’re correct, and if you can out-compete your rivals in the market for those consumers’ dollars, then your actions will have added wealth to society. This is profit-seeking.

On the other hand, if the rules say that it’s okay to use political means—the government’s authority to initiate violent aggression and fraud—to contrive rents by preventing others from competing with you or by forcibly taking the wealth of others, people will naturally tend to spend valuable resources trying to gain access to them. This is rent-seeking.

The main difference between the two is in the end result: profit-seeking creates wealth while rent seeking transfers wealth. When an economic activity creates wealth, both sides of the resulting exchange are better off. When an economic activity transfers wealth, only one side is better off, while the other side is worse off. In rent seeking, the corporations winning government “rents” are better off, but their competitors and taxpayers in general are worse off. In fact, we might even say that rent seeking destroys wealth, because it consumes resources spent in pursuit of government favors.

There are several ways corporations seek rents: through government subsidies, regulations that penalize their competitors, but the most egregious way is asking government to force consumers to buy their product or service. We've seen this happen repeatedly in the insurance industry, the members of which lobby to make certain types of insurance legally mandatory, including car insurance and, under Obama, health insurance.

Another interesting form of rent seeking is when pharmaceutical companies pressure the government to mandate drugs. Most people support this type of rent-seeking without really questioning it. They assume the vaccines are necessary for public health and see no other way to force others to take them.

In mandating vaccines, the government has created a $24 billion industry, and Technavio, a company in the business of predicting such things, estimates this number will grow to $61 billion in two short years. This isn't an industry big pharma has created. They couldn't; the demand for vaccines simply isn't as high as it becomes by legally mandating them. No, the government created this industry and big pharma is simply cashing in.

You may question the claim that demand for vaccines isn't high. It may be higher for the big three: polio, MMR (measles, mumps, rubella), and DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis) vaccines, but even for these three, demand is not as high as most people assume. In third-world countries, a lack of education is blamed for individuals and families choosing not to vaccinate. Here in the US, it's the opposite: individuals and families that refuse vaccines have usually done quite a bit of research on the drugs' side effects.

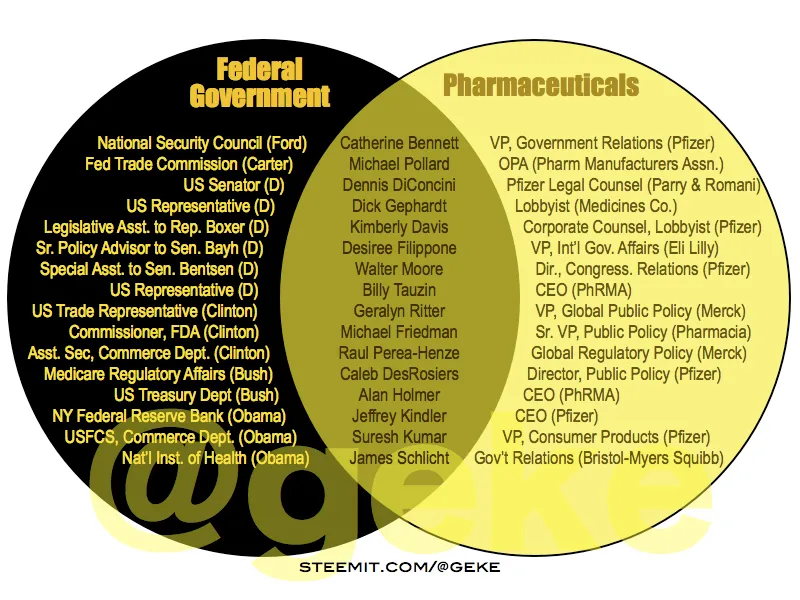

And this is true, despite the fact that advertising for these products isn't only managed by the pharmaceutical companies, themselves; the government is actively trying to increase demand for these products by recommending them through various government agencies. Why? Most people assume it's because the government is promoting public health. Some people in government may think they're doing that. But the bigger reason is because drug companies are embedded in the federal government, inside the FDA, the CDC, and in congressional committees that write and pass these laws in the first place.

And actual consumer demand for vaccines outside the big three mentioned above vary widely, including demand for easily obtained flu vaccines. One low-demand drug being heavily promoted, government-recommended, and increasingly discussed for legal mandate is the HPV (human papilloma virus) vaccine.

In fact, Gardisil, manufactured by Merck, is now mandated for girls in middle school Virginia, Rhode Island, and the District of Columbia. It was also mandated early on in Texas by executive order (later overturned) of then Governor Rick Perry, a move many blamed on Perry's revolving-door ties to Merck: Perry's former chief of staff and good friend, Mike Toomey, was a Merck lobbyist at the time Perry signed the executive order. (A GekeVenn for Merck will follow in its own separate, searchable post.)

Merck had been lobbying state legislatures to mandate HPV vaccinations, but they stopped their lobbying efforts in 2007. Why? They expained the move by saying their lobbying efforts were distracting them from more important business, but GlaxoSmithKline came out with their own HPV vaccine, Cervarix, in 2007. The Merck monopoly on HPV vaccines was over, and GSK was likely to begin lobbying efforts of their own.

But the story of the HPV vaccine is also interesting because it's a great example of a vaccination suffering from extremely low demand. In fact, due to its low demand, GSK has taken Cervarix out of the US market. The lesson? Vaccinations dont' enjoy the high consumer demand you might assume, and this is why rent-seeking behavior occurs with such vigor. The only way to create profitable demand in HPV vaccines is to legally mandate their use, and the same is true, to varying degrees, with other vaccines, as well.

However – and this is a big however – drug companies are starting to get wise to how self-lobbying looks. So they're creating new entities to do it for them, entities like NACCHO, the National Association of County and City Health Officials. NACCHO discloses the CDC as one of their funders, as well as the Immunization Action Coalition. When Oregon sponsored a bill to remove vaccine exemptions based on religious or philosophical reasons, members of the Oregon legislature reported that they were aggressively lobbied by NACCHO in support of the bill. Their position on the issue has been clearly articulated: “The National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) urges that personal belief exemptions be removed from state immunization laws and regulations.”

And in fact, their position on immunizations in general is extremely ambitious:

"The National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) urges the federal government to support the creation of a comprehensive national immunization program that addresses all stages of life (cradle to grave) with the intention of achieving the Healthy People 2020 immunization goals and standards. Such a program will help protect our nation's population from vaccine-preventable diseases by increasing rates of childhood, adolescent, and adult immunization coverage.”

Bringing vaccine mandates under the federal umbrella would certainly save vaccine lobbyists a lot of time, trouble, and expense. But considering the fact that NACCHO is funded largely by the CDC, you can see how incestuously centralized the business of vaccinations has become, and hopes to further become. The rent-seeking of corporations is turning into an internal government process.

used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license ]