Source

Source

All language students (Non-Native Speakers) who learn a second language out of its natural context, that is, as a foreign language, are afraid they may sound too bookish. The more isolated L1 society (mother language) is from L2 (second language) media and other inputs, the higher the chances of acquiring the textbook version of that language, without the pragmatic aspects, so needed in effective daily life communication.

In the case of Venezuela, we went from being a very anglicized culture to becoming one of the most anti-American nations (at least in the official discourse). The political and ideological animosities have isolated us from other English speaking countries such as England, Australia, or Canada. Our former booming tourism industry, which allowed people from all over the world to visit and mingle was ruined to the point that these days it is really hard to meet a foreigner in the streets, let alone an English-speaking one (Native Speaker).

In this context, learning English as a foreign language, becoming really fluent, is as difficult as getting the political actors to agree on any given topic. With slow internet services failing and becoming harder to afford by most people, without cable services providing programs in English, without native teachers, without English magazines or newspapers, and without English-speaking visitors, to learn the pragmatic aspects of the language becomes increasingly difficult.

Source

Source

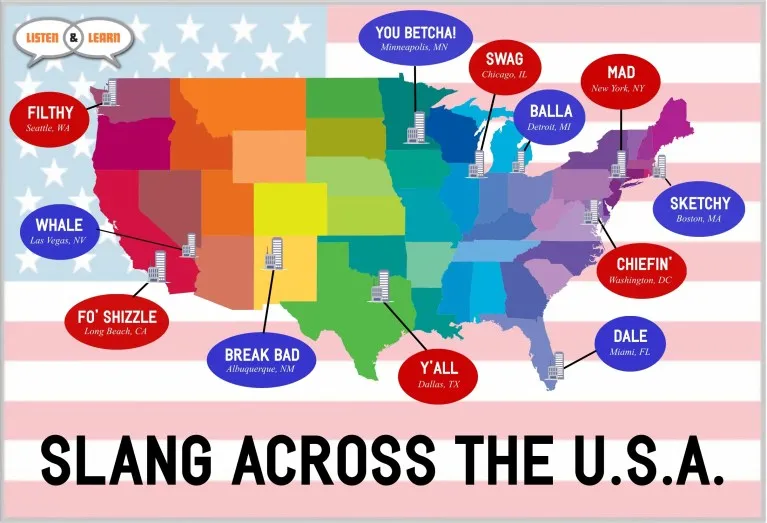

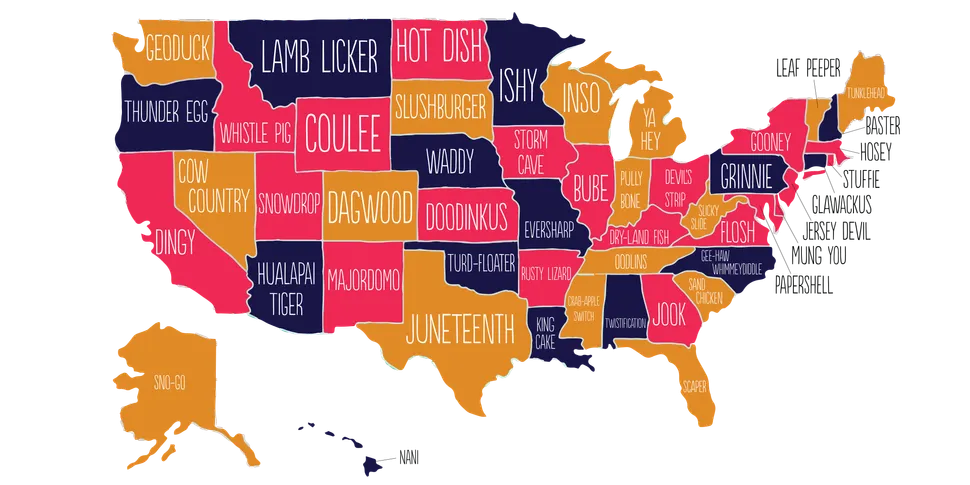

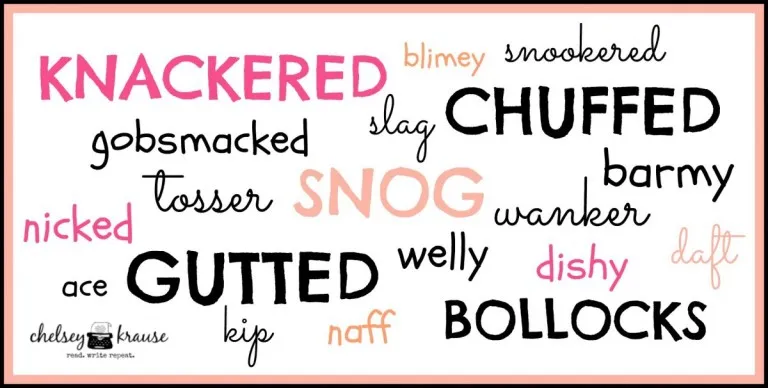

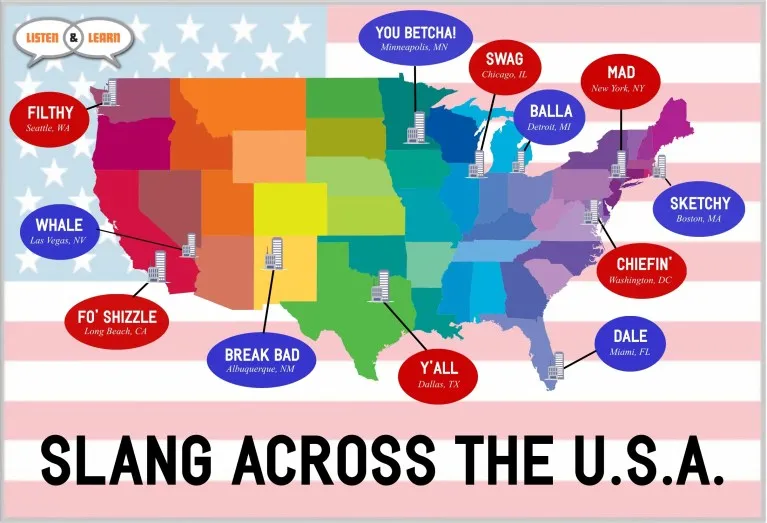

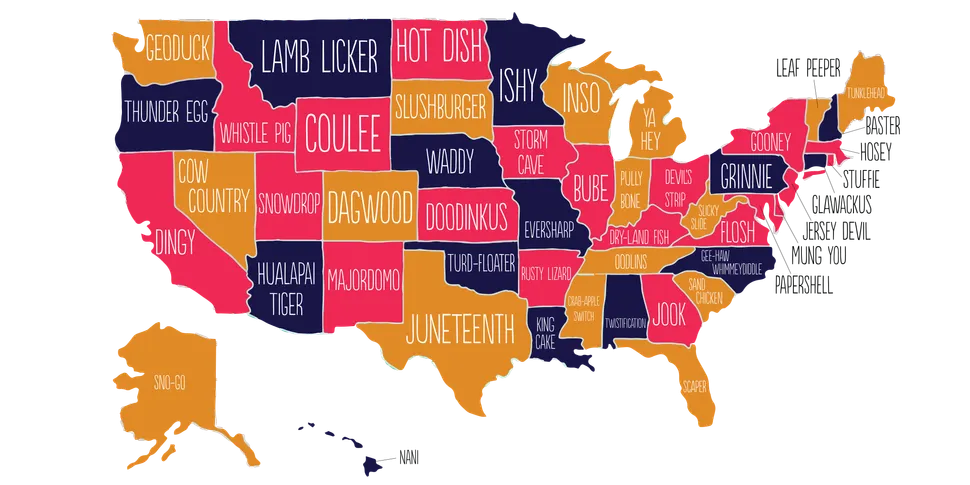

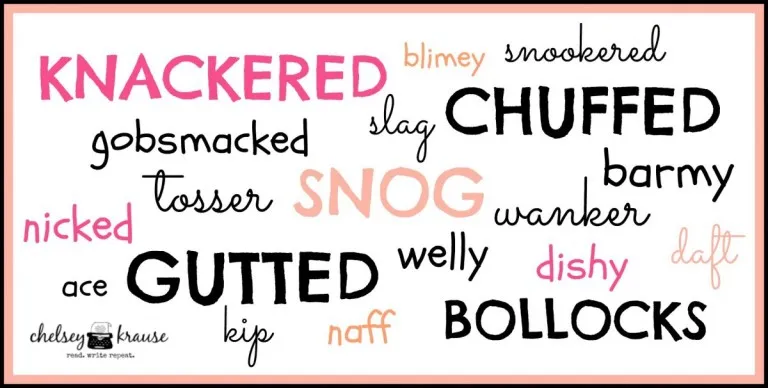

Idiomatic expression, idioms, or slangs are an integral part of any language. They provide refreshing informal culture-specific insights into the language being learned. They can also be the most complex aspect of any language, even for their native speakers. Slangs can vary from one region to another. Thus, no one in any given country knows the intricacies of regional variations of their language in depth. Now, some textbooks used in language teaching have progressively increased the number of common idiomatic expressions included in their corpora. However, the main problem with idioms is that they can change, come and go, pretty fast. If we add to that the impossibility of updating textbooks editions, then people may end up learning a rather passé form of language.

The greatest fear of a language learner is to face native speakers and not be able to understand them despite their years of learning. Most of the time, that fear in unfounded, but in many instances real-life conversation speed and informal expressions, along with local accents, can seriously compromise communication between NS and NNS.

Source

Source

Idiomatic expressions can be hard to teach because they pose semantic, grammatical, and syntactic challenges. By definition idioms are words or phrases whose meanings are established by usage and are hard to deduce from the literal meaning of their constitutive parts. The good thing is that idioms exist in all languages and even though they are hard to translate in most cases, sometimes they have equivalents in L1 that allow learners not only to understand the particular idiom being learned but also the way these expressions work.

Idiomatic expressions come in different shapes. They can be a word, such as “buck” (a dollar), which in Venezuela has an equivalent (bolo or lucas); a phrase, such as “to have a ball” (gozar una bola); or a sentence, such as “the shit hit the fan” (se armó el mierdero). Some idiomatic expressions allow certain changes and modifications without altering its meanings (she was having a ball), but not others (a ball was being had). That is why it is so important to have the exposure that would allow the learner to learn and use these expressions properly.

Source

Source

Not all idioms are vulgar, but many of them can be. Thus, information about meaning and context in which they can be used is important to spare learners embarrassing moments. In Venezuelan Spanish, for instance, you can use the greetings expression ¿Cómo está la vaina? among friends and acquaintances (= how is shit? How are things), but it would be impolite to use such greeting in front of people you just met, in formal context, or with people of higher social or professional rank. It works similarly in most languages, so it is important to provide learners with as much context, examples, and alternatives as possible. ¿Cómo está la cosa?, ¿Cómo le/te va?, or ¿Cómo está todo? Are all neutral and acceptable greetings for almost all occasions.

Some Hard-to-translate Idioms from Venezuelan Spanish:

Comerse la luz. Literally “to eat the light”, an allusion to traffic light, which means to cross a previously determined line, to abuse or disrespect, with the implied threat that something really bad can happen to you. No te comas la luz (do not eat the light) is a common threat these days. Se comió la luz (s/he ate the light) is a common explanation for someone’s tragic outcome.

¡Que molleja!. Exclamation, mostly used in the west part of the country, specifically by people from the state of Zulia. Possibly a corruption of the word mollera, which means the bland part or crown of the head, molleja became a polysemic word meaning several things. Its English equivalent may be close to “damn” or “fuck”, depending on the tone and context. Variations of the term include mollejuo, something that is very big, and mollejero, a street fight or turmoil.

Bajarse de la mula. Literally “to get off the mule”. It is an informal expression meaning to pay for something. At some point it was a feared expression because it was used by robbers to compel their victims to hand in everything of value they had (¡Bájate de la mula!). Among friends, it is used jocosely.

El año ‘e la pera. Literally “the year of the pear”. Hyperbolic expression used to suggest that something is unlikely to happen: when is he going to pay you back? el año ‘e la pera, that is never. Also, it is used to suggest that something is very old. un carro del año ‘e la pera (a very old car).

Ponerse Popy. This expression alludes to a famous children’s TV show clown (Diony López). Popy became the quintessential clown for Venezuelan kids, but also the slang for someone impertinent. ¿Te vas a poner popy? (are you going to play/turn the clown?) became a common question whenever someone tried to step back or have second thought about something, or whenever someone was acting stupidly, ruining a party or gathering. Se puso popy = s/he screw up.

It is hard to determine what language is more idiomatic or informal (I'd say all languages are), but the handling of idiomatic expression plays a vital role in any learner's ability to understand daily linguistic interactions and express in at the native speakers level. Thus, the teaching of idioms or slangs should be part of any language program.

Written by @hlezama

Click the coin below to join our Discord Server

We would greatly appreciate your witness vote

To vote for @adsactly-witness please click the link above, then find "adsactly-witness" and click the upvote arrow or scroll to the bottom and type "adsactly-witness" in the box

Thank You