Today, we’re back in the south of Sweden. Here’s a picture of the parish church in Mjällby, built in 1791, where many of my ancestors lived and worshiped. They married there, had their babies baptized there in the döpfont (I love that word!)

(Source)

Most of my more-intensive family history researching days are spent solving a mystery or unraveling a mixture of families that have been mixed together accidentally. Today’s puzzle involved a Karna Trulsdotter in my family line in the 1700s (before the above church was even built.)

I noticed that somehow this person had three spouses with 11 different children interspersed between the husbands, but overlapping… That doesn’t work, so on a piece of paper (and then a Libre Office file) I sorted them out starting with the husbands. The key to sorting out this kind of match is records.

There is a saying in genealogy:

Genealogy without proof = mythology.

So, I needed to sort out the proof from the mythology.

Finally, I found the marriage records (hard evidence) for both of the main two husbands. One was married to a Karna born in 1729. The other’s Karna was born in 1737. Okay, two Karna Trulsdotters, in the same area, both having children fairly near each other in time. Perfect recipe for confusion!

Thankfully, due to the patronymic naming scheme of the time, it was fairly simple to sort out this group and then sort/merge the correct people on Family Search as well. ALL the relevant people now have warnings at the top of their profiles to watch out for the other!

So, since we’re talking about names, let’s talk about…

Patronymic names

Patronymic names are when a child receives a surname based on the first name of the father.

The son of John is John’s son = Johnson.

In Swedish, these names take this format:

Per’s son = Persson (The first ‘s’ is the possessive before the word ‘son’)

Per’s daughter = Persdotter

Simon’s son = Simonsson

Simon’s daughter = Simonsdotter

(Note: in Norwegian and Danish, it becomes Simonsen and Simonsdatter instead. Icelandic, I believe it’s Simonsson still, but Simonsdottir. At this point, though, I’ve not done any work in Iceland.)

This patronymic system was phased out in the 1800s which is really important to note because you can sometimes see all three different versions in place in official records! So, when Karna married Per Jonsson, her daughter Bengta could be called: 1. Bengta Persdotter (traditional), 2. Bengta Persson or even 3. Bengta Jonsson (modern)!

Several other things began happening as names began changing.

Sometimes, they added an occupation name to the surname. So, Jon Persson who was a hat-maker became Jon Persson Hattmakare (hat-maker) or Nils Larsson who was a scribe became Nils Larsson Skrika. These names were sometimes passed down, sometimes not, but they helped to distinguish between others of the same patronymic name.

Other times, they added a place name. I’m not aware if this is a “farm” name in Sweden as it is in Norway, but it very well may be. In any case, this place name could easily move along with them when they left – and was often passed down to the children – at least until the children left the area.

In all of these cases, you can easily end up with multiple names that all belong in the Surname box of you genealogy program. Don’t be afraid to use them all – though at the end of the day, if you can find the birth name, that’s the one that actually belongs in the Surname box, the others are aliases.

Here’s a good record to share to show you some names…

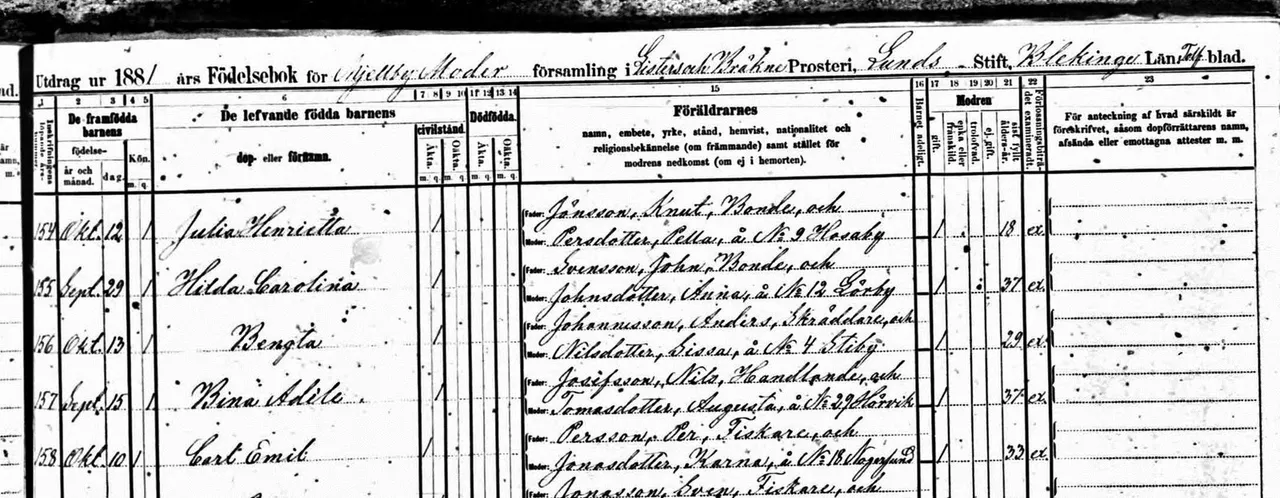

(Image from my personal family tree on Ancestry.)

A “birth book” (födelsebok) from the Mjällby parish in Blekinge.

Across the top, we have:

- the birth date

- number of babies of which gender

- their first name or “Christian name” (döpnamn)

- whether it was a live birth or a still birth (dödfödda)

- the parents’ information (note how there’s way too much stuff being asked for the space! Name, work, town, religion, etc, etc. They clearly only put a little bit of information. These folks are largely farmers (bonde) and fishermen (fiskare).

- It also asks whether the parents are married (gift) and for the age of the mothers.

Today’s DON’T

People sometimes think they’re being really clever by putting the patronymic-assumed first name of the father in box. So, my Larsdotter ancestor had “Lars” put into the father’s box by someone being clever.

It’s actually not very helpful. Why? See above where I talk about how things have changed. If you assume, you’re also assuming that nothing changed – or that they didn’t use the woman’s married surname in the box… Wait until you have the document or source to prove who her father really was!

That’s it for today’s edition of Records and Reason – feel free to ask me a question in the comments section and I’ll include it in next week’s issue.

(Cover image from PxHere

Today’s post is crossposted at: Steemit, Whaleshares and WeKu

author/designer at A'mara Books

photographer/graphic artist for Viking Visual

crossposting at: Steemit, Whaleshares and WeKu

Banner by @shai-hulud