The gut flora or gastrointestinal microbiota are important for our health. They are not simply co-existing inside of us, but have a mutual symbiotic relationship with our bodies. When our gut flora is out of whack, we can experience inflammation in the GI tract and even develop autoimmune conditions.

What we eat matters. Diet changes effect the microbiota and our overall health. Recent research has also linked healthy gut bacteria to a healthy brain, relating it to autism and Alzheimer's. It seems the tiny microorganisms have a huge impact on our health.

Source

It's not only diet or antibiotics that can positively or negatively effect the microbiota in our gut, but exercise too. The first definitive evidence of exercise alone changing gut flora has been shown in two studies. One study on mice involved transplanting fecal material from exercised and sedentary mice into the colons of sedentary mice who had no microbes. The other study was on humans which measures the microbial changes as lean and overweight people went from a sedentary to a more active exercising lifestyle, and then back to not exercising again.

Source

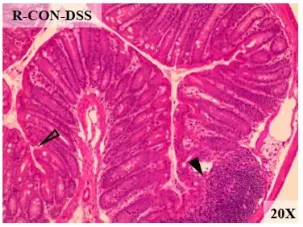

Mice who received gut flora from other mice showed the same changes in their microbiota levels, with a difference in the microbes from exercised or sedentary mice. Those receiving exercised microbes were producing higher levels of butyrate which is a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) that promotes healthy intestinal cells, reducing inflammation and increasing energy. These mice also were more resistant to an inflammatory bowel disease (IBS) called ulcerative colitis, as they had reduced inflammation and quicker recovery from exposure to a colitis-inducing chemical.

The human study had 18 lean and 14 obese participants. Their gut microbiomes were sampled before exercise, again after a 6-week exercise regiment of 30-60 minutes 3 times per week, and one last time after another 6 weeks of sedentary behavior. No diet changes were made at any time. Short-chain fatty acid fecal concentrations went up as a result of exercise, especially the butyrate, just like in mice. But after a sedentary lifestyle was resumes, those concentrations fell.

Body size (lean vs. obese) had an effect on the level of microbiota as well. Obese participants had only a moderate increase in SCFA-producing microbes compared to lean people. Lean people had lower levels of these microbes to begin with, but had a more dramatic increase from exercising. More work is required to determine why there are different responses in the gut microbiota levels for lean or obese people who exercise.