Te Rauparaha

A name feared by both opposing Maori and Europeans.

Said to have been a boy when Captain James Cook was in New Zealand, so he was probably born in the 1760s.

He was descended from Hoturoa, with Werawera of Ngati-Toa as his father, and his second wife Parekowhatu as his mother, although not born of the highest rank, he became the leader of the Ngati-Toa because of his aggressive defence of his tribe's interests and his skill in battle.

He was short in stature, but of great muscular strength.

His name was derived from an edible plant ‘Rauparaha’, soon after he was born a Waikato warrior had killed and eaten a relation of his, and threatened to eat the child as well, roasted in Rauparaha leaves, the child was called Te Rauparaha in defiance of this threat.

[Also known as Shore Bindweed]

The other name he was called during his childhood was Maui Potiki, because he, like his namesake, was lively and mischievous

His childhood was spent at Maungatautari and Kawhia.

From the late 18th century Ngati-Toa and related tribes, including Ngati-Ruakawa, were constantly at war with the Waikato tribes for control of the rich, fertile land north of Kawhia.

The wars intensified whenever a major chief was killed, or insults or slights suffered.

Te Rauparaha was involved in many of these incidents as tensions mounted, he led a war party into disputed territory north of Kawhia and the Waikato chief Te Uira was killed.

On another occasion he led a war party by canoe to Whaingaroa [Raglan Harbour] to avenge the killing of a group of Ngati-Toa, his nieces had been among the victims.

Young warriors gathered around him because he was an aggressive war leader.

As warfare intensified Ngati-Toa killed Te Aho-o-te-rangi, a Waikato chief, who had led an attack on Kawhia.

Te Rau-anga-anga led a large war party to avenge his killing, the Ngati-Toa were driven back to the Pa [fortified village] of Te Totara, at the southern end of Kawhia Harbour, where peace was made.

This peace was broken again shortly after when Te Rauparaha led a fishing party into waters claimed by Ngati-Maniapoto, Waikato came to the assistance of Ngati-Maniapoto and took the Pa of Hikuparoa, after a feigned retreat.

Te Rauparaha escaped to Te Totara Pa and after much fighting, peace was restored.

Te Rauparaha left Kawhia after this episode, but on his return, he joined a war party seeking revenge for the death of a prominent Ngati-Toa warrior, Tarapeke, who had died in a duel outside Te Totara Pa.

Under Te Rauparaha’s command, the war party went north and killed Te Wharengori of Ngati-Pou. This gave Waikato the excuse to once again invade Kawhia, and after defeat in some battles, the Ngati-Toa retreated to Ohaua-te-rangi Pa, where a settlement was made through his sister.

During times of peace, Te Rauparaha travelled widely to visit tribes friendly to Ngati-Toa, and he was at Maungatautari when Ngati-Ruakawa chief Hape-ki-a-rangi died, and he became his successor by responding to the dying chiefs query, “Who will replace me?”.

None of Hape’s sons or relatives responded, Te Rauparaha later took Hape’s widow, Te Akau, as his fifth wife.

Between 1810 and 1815, Te Rauparaha was with the Ngati-Maru, in the Hauraki Gulf and was given his first musket.

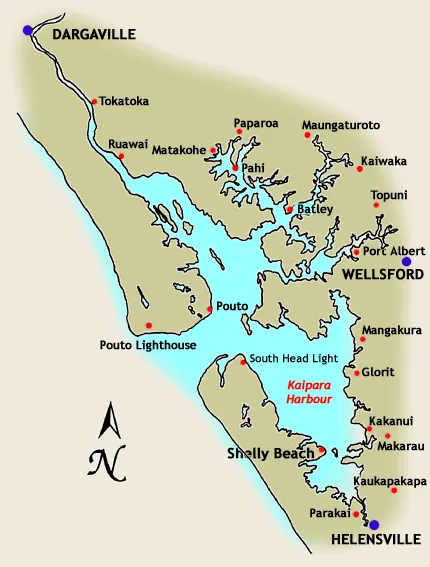

He also visited Ngati-Whatua at Kaipara, where he was probably looking to build a coalition to attack Waikato, or perhaps looking for a place where his tribe could settle.

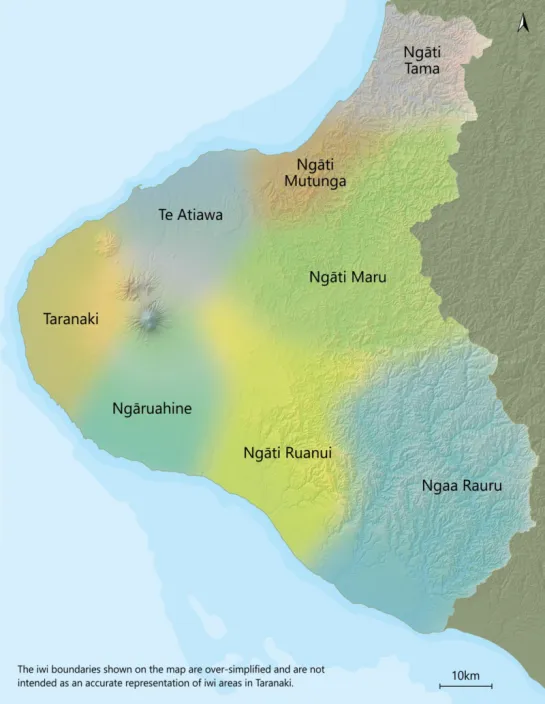

The Ngati-Toa had long-standing alliances with the tribes of northern Taranaki, the southern neighbours of Maniapoto, and in 1816, the marriage festivities of Nohorua, Te Rauparaha’s older half brother, and a woman of Ngati-Rahiri, turned to disaster, when the canoes of Ngati-Rahiri, carrying a return feast, overturned.

In fury, Ngati-Rahiri attacked Ngati-Toa, two chiefs from Ngati-Whatau, from north of present-day Auckland, joined Ngati-Toa’s retaliatory raid in 1818.

Peace was restored at Te Taniwha Pa, and as part of the peacemaking, muskets were fired for the first time in Taranaki.

In 1819 Te Rauparaha joined a large northern war party, armed with muskets, led by Tuwhare, Patuone and Nene.

This war party went through the lands of Te-Ata-Awa, who were Ngati-Toa allies, and attacked Ngati-Maru-whara-nui of central Taranaki, Te Kerikeringa and other Pa’s fell to them. Warriors who had never encountered guns before became demoralized.

In his manner, the war party continued south to Cook Strait, where they saw a sailing ship pass through the Cook Strait, and Te Rauparaha was told that if he went south he could become great by trading with those ships for muskets.

On their way back they also fought with Ngati-Apa in the Rangitikei, and Te Rangihaeata, Te Rauparaha’s nephew, captured Te Pikinga of the Ngati-Apa and made her his wife.

On reaching Kawhia the Nga-Puhi gave muskets to Ngati-Toa and continued on their way north.

About this time, his wife, Marore was killed while attending a funeral in the Waikato.

In revenge, he and her relatives killed a Waikato chief on a pathway where travellers had safe conduct.

In 1820, several thousand Waikato and Ngati-Maniapoto warriors invaded Kawhia, the Ngati-Toa was defeated at Te Kakara, near Lake Taharoa, and Waikawau Pa, south of Tirau Point, was captured.

Te Rauparaha retreated to Te Arawi Pa, near Kawhia harbour, which was besieged.

Among the besiegers were relatives of the Ngati-Toa, who did not want to see the tribe exterminated, so they secretly supplied food to the Pa, and advised Te Rauparaha to seek refuge with Te-Ati-Awa in Taranaki.

Te Rauparaha had considered fleeing east to his Ngati-Ruakawa relations but the way was blocked by hostile forces, eventually, due to many having close relations in the Waikato tribes, they were allowed to leave Kawhia and begin their migration south.

Te Rauparaha burned his carved house and recited a lament for Kawhia, then the Ngati-Toa went a few miles south to the Pukeroa Pa, where the people were related to both the Ngati-Toa and the Ngati-Maniapoto.

Most of the women and children with the injured warriors were left there while the warriors continued further south and crossed the Mokau river into the area of their Ngati-Tama allies.

Te Rauparaha then took a party of 20 warriors, armed with muskets, to bring out the women, children and injured warriors that he had left behind.

He knew that the Ngati-Maniapoto had followed him, so he dressed his party in red cloth and spread a rumour that a Nga-Puhi war party, dressed in red, was in the area.

The Ngati-Maniapoto stayed well away from the supposed Nga-Puhi war party.

That night, while waiting to cross the Mokau River, Te Rauparaha addressed imaginary groups of warriors, lit many fires, and spread cloaks over bushes to give the impression of a large war party.

Re-united south of Mokau, the 1,500 Ngati-Toa went to Te Kaweka, in Taranaki, to cultivate land given to them to use by Te-Ati-Awa.

A Waikato force, led by Te Wherowhero, came south but was defeated at the battle of Motunui in late 1821 or early 1882, and freed Ngati-Toa from the threat of pursuit.

Te Rauparaha left Ngati-Toa in Taranaki and returned north to Maungatautari, to try and persuade Ngati-Ruakawa to join his migration, because he needed more fighting men.

But they had other ambitions in Heretaunga [Hawkes Bay], so he went on to Rotorua, and encouraged Te Arawa to attack a Nga-Puhi war party, to avenge the killing by the Nga-Puhi of his Ngati-Maru relations.

Some of the warriors joined him and went back to Taranaki with him.

In 1822 the next part of the migration continued, he was joined by some of the Te-Ati-Awa people and they travelled 250 miles through hostile land that he had conquered several years before.

At first, the migration was peaceful because Te Rauparaha had made peace and marriage alliances with some tribes.

Others, having learned to fear war parties with muskets, and distrusting his motives.

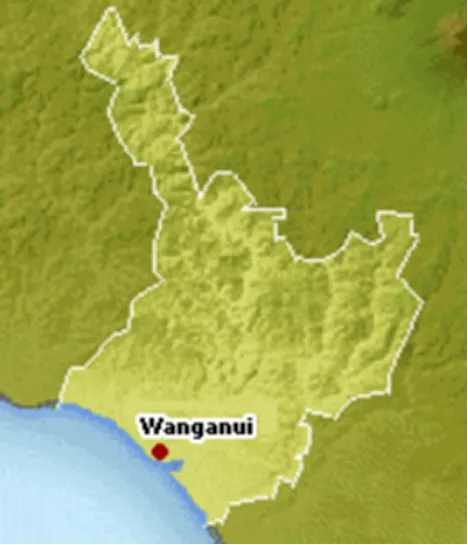

The Wanganui tribes withdrew upriver, and in the Rangitikei, the Ngati-Apa were at first friendly as they were related to Ngati-Toa by the marriage of Te Pikinga to Te Rauparaha.

Trouble began when the migration reached the Manawatu River, canoes were stolen when Nohorua led a foraging party.

In retaliation, Ngati-Toa attacked a Rangitane settlement and killed several people.

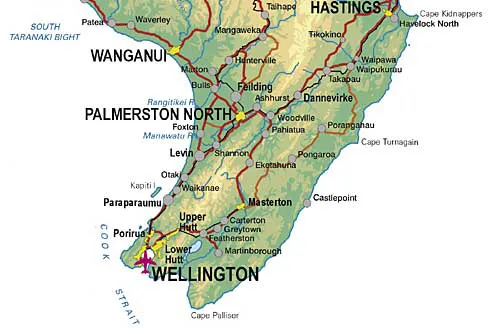

The tribes of Manawatu and Horowhenua began to resist, Toheriri of Muaupoko invited Te Ruparaha and his family to a feast near Lake Papa-I-Tonga, near today’s Levin,

When night fell Muaupoko began killing them, Te Rauparaha escaped but his son Te Rangi-hounga-riri and his daughter Te Uira and at least one other of his children were killed.

Te Rauparaha vowed to kill Muaupoko from dawn until dusk, the lake Pa of the Muaupoko was taken and they were massacred without mercy.

While Te Rauparaha was attacking the Horowhenua tribe, Te Pehi kupe, the senior chief of the Ngati-Toa, surprised and attacked the Muaupoko on the island of Kapiti and captured the island.

As the Ngati-Toa were threatened by both Ngati Kahungunu and Ngati-Apa they moved to Kapiti for security.

A great canoe fleet assembled in 1824 with contingents from Taranaki to Wellington Harbour in the North Island, and from the South Island.

A night attack was made on Kapiti at Waiorua which was defeated, this established Ngati-Toa firmly in the south of the North Island.

Allies from Taranaki and Ngati-Ruakawa joined Te Rauparaha in numerous migrations over the next decade and were found land in the conquered territories.

Whalers and other European ships had been trading at Kapiti and Te Rauparaha’s power over his allied tribes rested on his control of the trade in arms and ammunition.

Captives were taken to Kapiti to scrape flax to be traded for muskets, powder and tobacco.

He also wanted to control the supply of greenstone, and, the South Island, where the greenstone came from, this Island was open to conquest as the tribes there had not yet acquired guns.

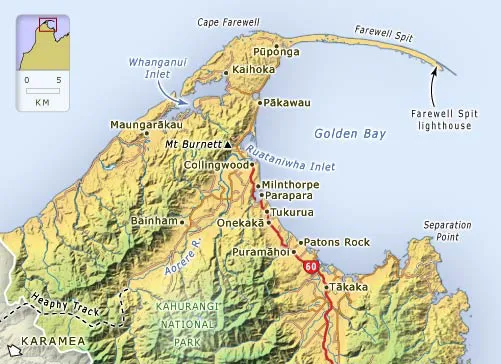

Some of their chiefs had insulted him and some had fought against Ngati-Toa at Waiorua, so in 1827 Te Rauparaha took a war party across Cook Strait to Wairau, where several Rangitane Pa’s were taken.

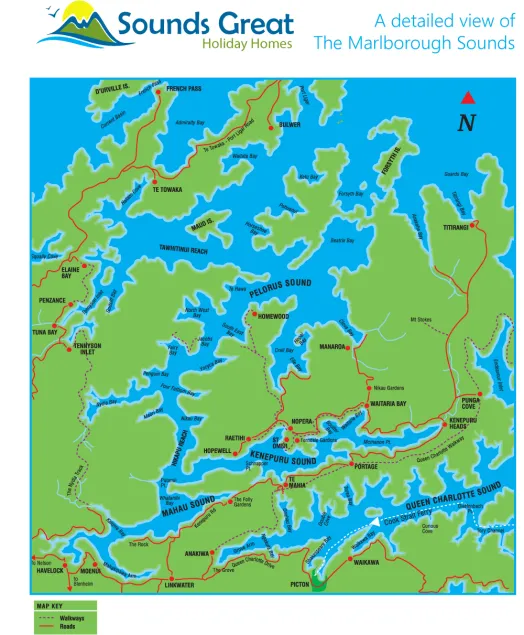

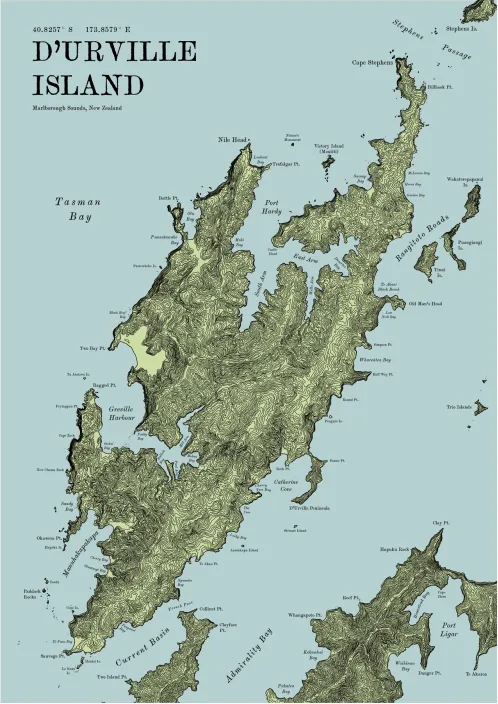

The following year, a larger invasion fleet left Kapiti, Te-Ati-Awa attacked the area around Te-Ara-a-Paoa [Queen Charlotte Sound], while Te Rauparaha, with 340 warriors mostly armed with muskets, entered Te Hoiere [Pelorus Sound] and heavily defeated Ngati-Kuia at Hikapu.

At Kaikura many Ngati-Tahu were surprised and killed or enslaved.

Te Rauparaha led part of the war party to the Ngati-Tahu stronghold, Kaiapoi Pa.

Image Source

Te Pehi Kupe and 7 other Ngati-Toa chiefs entered the Pa to trade for greenstone.

The people at Kaiapoi knew of the attack on their relations at Kaikura, and the Ngati-Toa chiefs were killed and eaten.

Ngati-Toa then unsuccessfully attacked the Pa and killed about 100 Ngati-Tahu prisoners.

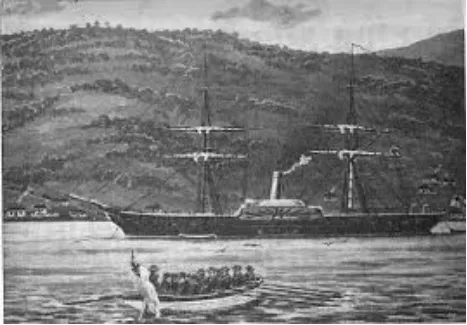

In 1830 the attack on Ngati-Tahu was resumed with Captain John Stewart taking about 100 Ngati-Toa to Akaroa in the hold of his ship, the brig ‘Elizabeth’.

The chief of the Ngati-Tahu, Tama-i-hara-nui, his wife and daughter, were lured aboard the ship, captured and transported to Kapiti and killed,

On the ship, Tama killed his own daughter to prevent her from being enslaved.

Also in 1830 Te Rauparaha went to Sydney, Australia, where he met Samuel Marsden, the chaplain for New South Wales.

The ship that returned him to Kapiti is said to have taken him to Rangitoto [D’Urville Island], where he captured Ngati-Kuia refugees, and had then transported to Kapiti Island.

In 1831 Te Rauparaha again besieged Kaiapoi Pa, and captured it by sapping it and firing the palisades, he then returned to Akaroa and took the Onawe Pa, then returned to Kapiti, leaving some of his allies and some of his own people to rule over the enslaved tribes.

Meanwhile the migrant tribes in the southwest of the North Island, none of whom had accepted Te Rauparaha’s authority, were competing with each other and the original inhabitants for land and resources.

Fighting broke out between Ngati-Ruakawa and Te-Ati-Awa in 1834, this threatened Te Rauparaha’s leadership, as he was allied to Ngati-Ruakawa,

Other Ngati-Toa, led by Te Hiko-o-te rangi, the son of Te Pehi Kupe, supported Te- Ati-Awa and besieged Te Rauparaha at the Rangiuru stream.

He was forced to appeal to the Ngati-Tuwharatoa chief, Mananui Te Keukeu Tukino 2nd for help.

When peace was restored Te Rauparaha intended returning north with Mananui, but was persuaded to remain and went back to Kapiti.

By mid-1830’s Te Rauparaha and his allies had conquered the southwest of the North Island and most of the northern half of the South Island.

He wanted to extend his conquest to the rest of the South Island, but Ngati-Tahu had obtained muskets from the whalers in Otago and were able to resist him.

He was nearly captured at Kapara-te-hau [Lake Grassmere], [Marlborough]and fought inconclusive battles at Oraumoa-iti and Oraumoa-nui in present-day Marlborough, in January 1833.

After Te Rauparaha’s sister, Waitohi died in 1839, war broke out among the tribes allied to Te Rauparaha,

A large funeral gathering was held and a slave of Te-Ati-Awa, who had brought tribute from the South Island was killed and eaten, against Te-Ati-Awa’s wishes.

Quarrelling at the feast led to renewed fighting between Te-Ati-Awa and Ngati-Ruakawa, culminating in the battle of Te Kuititanga at Waikanae.

Te Rauparaha crossed over from Kapiti to assist Ngati-Ruakawa, but had to escape in a whaling boat when they suffered a severe defeat.

After the battle, there was no looting of the dead, or cannibalism, as Christian influences had been brought to the Te-Ati-Awa by freed slaves returning from the Bay of Islands.

The Ngati-Ruakawa dead were buried with their clothing and weapons and ammunition.

Later in the day, [16 October 1839] the New Zealand Company ship ‘Tory’ arrived at Kapiti, Colonel William Wakefield wanted to buy vast tracts of land.

Negotiations took place and Te Rauparaha accepted blankets, muskets, and other goods for the sale of land, the extent of which would become a matter of dispute later on.

He insisted that he had only sold Whakatu and Te Taitapu in Nelson and the Golden Bay area.

All land sales were declared null and void by Lieutenant Governor William Hobson after his arrival in 1840, and a commission was set up to investigate land claims.

On 14 May 1840, Te Rauparaha signed a copy of the Treaty of Waitangi presented to him by Missionary Henry Williams, believing that the treaty would guarantee him and his allies the possession of the lands gained by conquest over the last 18 years.

He signed another copy of the Treaty on 19 June 1840 when Major Thomas Bunbury insisted that he do so.

Te Rauparaha resisted European settlement in those areas he claimed not to have sold, disputes occurred over Porirua and the Hutt Valley, with the major clash being in 1843, when Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata prevented the survey of the Wairau Plains.[Marlborough]

Arthur Wakefield led a party of armed settlers from Nelson to try and arrest Te Rauparaha.

Fighting broke out, during which Te Rongo, the wife of Te Rangihaeata was killed.

After the settlers had surrendered Te Rauparaha had them killed to avenge her death.

In the crisis that followed Te Rauparaha stayed on the defensive, there was a reluctance for a war among those influenced by the missionary Octavius Hadfield, at Otaki.

Te Rauparaha had much to lose if he attacked European settlements, the settlers believed that he had sent for a Wanganui war party to attack Wellington, as the Te-Ati-Awa of Waikanae had refused to do so.

The crisis was ended on 12 February 1844, when Governor Robert Fitzroy declared, at Waikanae that the settlers had provoked the fighting at Wairau, and although he deplored the killing of the settlers, no further action would be taken.

During this crisis Te Rauparaha, by avoiding war with the settlers, contributed greatly to its peaceful conclusion.

On 16 May 1846, Te Mamaku, of Wanganui, who had joined Te Rauparaha in resisting settlement, led an attack on the troops stationed at Almon Boulcott’s farm in the Hutt Valley.

There were again rumours of an imminent attack on Wellington, the new Governor George Grey, decided that Te Rauparaha could not be trusted and must be arrested.

He visited him in his Taupo Pa, near Porirua, and left on the naval ship ‘Driver’.

Two hours before dawn, the ship returned and British troops took Te Rauparaha aboard.

He was held on another naval vessel, the ‘Calliope’ for 10 months, then allowed to live in Auckland.

On his petition to the Governor, he was allowed to return to his people in Otaki in 1848, he accompanied by George and Eliza Grey on his return journey.

Te Rauparaha remained for rest of his life there, with short trips to Wairau, and by the end of his life, his influence appears to have declined, possibly by the humiliation of being a prisoner for so long.

He died on 27 November 1849 and was buried near the church, Rangiatea, Otaki, although, he may have been re-interred on Kapiti Island.

He had 8 wives, in the course of his life, and 14 children, some of whom survived him, and while he went to church he did not adopt Christianity.

He was a great tribal leader, taking his tribe from defeat at Kawhia to the conquest of the southwest North Island, without his leadership Ngati-Toa would not have attempted the great migration, and in so doing, they changed the tribal structure of New Zealand forever.

@len.george/the-spread-of-the-descendants-of-hoturoa

@len.george/tainui-canoe-travels-from-hawaiki-to-new-zealand

@len.george/myths-and-legends-of-new-zealand-intro

@len.george/how-this-series-began

@len.george/the-warrior-deeds-of-kaihuma

@len.george/how-kaihamu-killed-his-enemies-at-waiatapu

@len.george/tupahau-goes-fishing-at-marokopa

@len.george/maki-s-battles-in-tamaki

@len.george/karewa-s-fights-with-the-ngapuhi

@len.george/the-continuing-battles-of-the-tainui-people

@len.george/the-story-of-maru-tuahu

@len.george/continuing-maru-tuahu-s-story

@len.george/kiki-and-tamure-the-two-sorcerers

with thanks to son-of-satire for the banner