May is certainly my favorite month, I keep realizing around this time, especially having been out of the 4-season temperate climate for more than a decade. After what seemed like an endless back and forth between Winter and Spring, finally the entire landscape has grown into a lush deep green, with plenty of flowers, birds, and bugs, oh my! Even though I am not doing any gardening myself right now, I can't help think about the diversity I keep seeing around me, and even the things I don't see. Which tree is that piece of pollen from that's floating past me int he air? Where did this bumblebee dig its hole? Which bird is going to eat that mosquito that I decided not to kill, just shooed it away from my arm?

What's the Point of Diversity Again?

While Permie minded folks will no doubt understand my excitement about nature's abundance and diversity, outside of this context one may wonder: What's the point of diversity? After all, having a well trimmed lawn in front of our house should be enough to kick the ball around, right? And true enough, if that's all you want to do, you may not even need that much. There are lots of artificial lawn-lookalikes that you won't even have to mow! But when it comes to food production - which I would extend to living with and in nature - a bit of biodiversity goes a long way... and lots of it will offer enormous benefits.

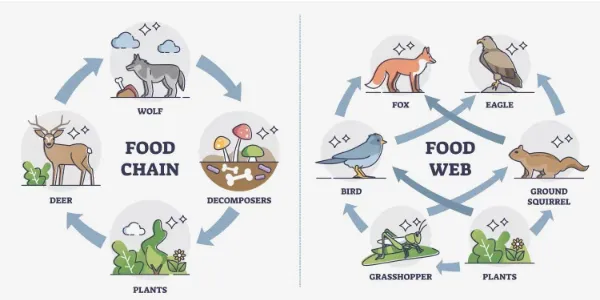

The Food Web: Our Relationship To Each Other

When interacting with nature, one of the most essential things to keep in mind is always: what does one particular species eat, and in turn what likes to it them. With this information we will start seeing each element as an individual who performs a certain function, just by following its most natural inclination (leading to the next important question of how do they go about doing it). It is up to us to utilize their work in certain parts of the ecosystem we live in, and help manage.

Upon closer observation, we will realize that the interaction of species has many levels. Some may not actively eat others, but they will compete against them, even to the point of completely overtaking their space (trees and walls covered in ivy is such a typical case). On the opposite end, others will cooperate, so much so that they may entirely depend on one another (just think of the example of many fruit trees who have evolved with the honey bees as their pollinators). Some species are successful parasites, affecting their victims by taking advantage of their live bodies rather than killing them. Of course, many species are perfectly neutral with each other, though they still affect each other indirectly by other aspects of their lives. No matter what the relationship individually is, the presence of each species will ultimately benefit the entire system.

Resistance to Plagues, Pests, and Famines

Naturally all species try to occupy a niche, the bigger the better. The only thing keeping them from taking up everything that's available is other species, which is quite important: because one species will be vulnerable to being taken out by one simple factor they are not prepared for. So having various other species eating one, while that one is also feeding on a number of species, creates a system that is stable enough to withstand sudden changes in their conditions, whether they are climatic, or have more to do with the composition of their ecosystem. In the end, a stable and dynamic system with a great diversity of life, is also most likely to produce most abundantly. We just need to keep in mind that what we consider "yield" of the garden needs to be just as diverse.

Too much of one thing is rarely a blessing, even if it happens to be our favorite food. Just think of a swarm of grasshoppers eating up every green leaf in sight, or a fungus decimating an orchard. When things have gotten this bad, fighting back by yourself is not only futile, it will most likely be counterproductive, as it takes out merely the weakest elements, giving the survivors a chance to reproduce. What works much better instead, is inviting the natural predators of whatever you have too much of, to help out in controlling them. Not a slug excess but a duck deficiency, as Bill Mollison put it. Fortunately, most species will come voluntarily, without needing to be bought, fed, and actively taken care of... IF they are cordially invited.

It's Not Food, It's Shelter They Need

So how do we tell wild plants, insects, birds, and even mammals to come and take up residence on our land? It may be counterintuitive, but offering them food alone is rarely enough to do the trick. They may partake of it, but if there is no other reason to stay, they will soon move on to greener pastures (provided it's the green pasture they are most happy with). However, if they find that along with the food you also offer them a place to hide, sleep, even have babies they will be more than happy to relocate to your garden permanently. This is why I am always happy to see insect-boxes, usually in community gardens throughout the city.

Of course, what works on the small scale can work on the large one. We just need to figure out (by observing) which outside factors they need exactly. Is it an island on a pond to lay their eggs? Is it a pile of rocks in the sun, where they can enjoy the heat of the sun? Is it a hole in the tree or in the ground to make their burrow? Could it be a little nook where they are safe from your cat? Whatever it is, if you build it, they will come. And once they are there, they will do everything in their ability to make your place work in their favor... which in the end is most likely what your place needs.