I think the image shows my age. I am not sure how many "youth" would be using a suspension folder system to organize their important documents, and bills. Yes - I still get about half my bills in paper format. I am a dinosaur. This is doubly "embarrassing" as I work in the field of information management. But, what I think it is more is that I don't have a lot of the digital habits that younger people have.

I still remember using cash.

I still use cash.

When I came to Finland over twenty years ago, it was already well on the way to a cashless society and the majority of people only used cards already. A big part of the reason for this was that POS transactions were free, with no fees on how many transactions were made. In Australia at the time, using the card came at a cost, including taking money out of autotellers. Banks would offer things like "8 free transactions" - but after that it was between 1 and 2 dollars each. Ludicrous.

But, using cash has many benefits, with the main one being that it is possible to purchase something, without being completely visible. But, the thing I brought up with my friends twenty years ago, was that using cash made spending a physical act, one that brought with it a sense of loss. Pushing this out into a digital transaction made spending money a proxy action, indirect and not visible in the moment. Especially back then, there were no mobile apps for banking, as smartphones didn't exist.

And, at least as I predicted back then, this has had a profound effect on the culture around money. When I first arrived, hardly anyone had a credit card they used and those who had one, used it for emergencies, not daily. Most people had the mentality of "only spend what you have", so personal debt outside of mortgage was low, and even mortgage debt was low, as the expectations on what was required in a house were also far more conservative.

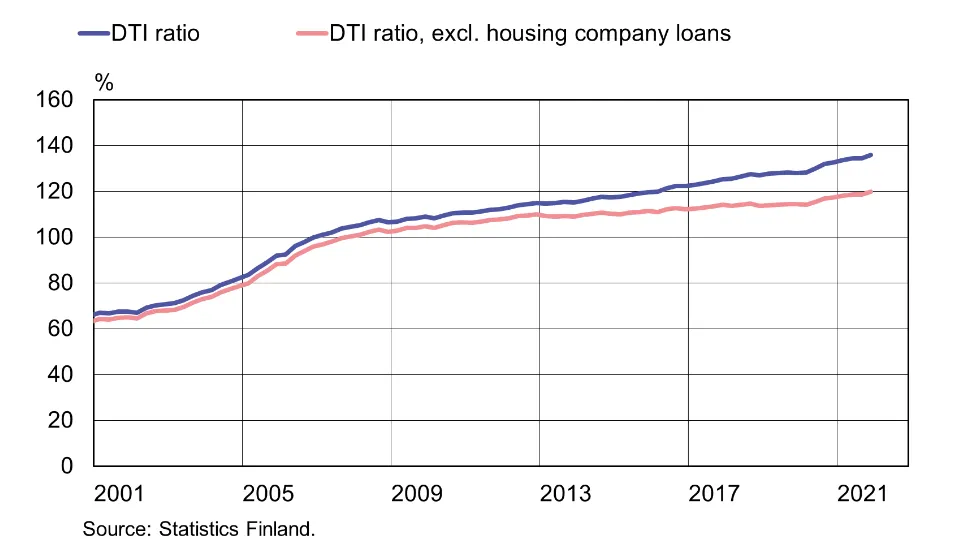

DTI = Debt to Income ratio. So, if a household earned 100K and had debts of 100K, it would be a 100% DTI. If the debt was 50K it would be a 50% DTI and if it was 150K, it would be a 150% DTI. This is an average across households, which means that there are far greater extremes if you consider that an older household would likely earn more and have less debt on their house. But a younger household will earn less and wouldn't have paid off their mortgage. "housing company loans" isn't mortgages, it is the debt that is paid monthly if living in an apartment, where the complex has loans that need servicing too.

Interestingly, Statistics Finland stopped publishing credit card debt numbers in 2013.

But as you can see, the debt ratio in Finland has been steady rising and in the space of two decades, has over doubled. This is "quite a change" in the culture surrounding money usage, isn't it? The normally thrifty Finnish mentality is increasingly succumbing to the spend now, consumer mentality of have now, pay later.

However, what is interesting when looking at how people talk about the DTI in the US, they look at it from the perspective of debt servicing to income. So, if a person earns 100K and spend 20K on debt per year, they have a ratio of 20%. This is a bit of a problem though, isn't it? For instance, if you are earning 100K this year and your ratio is 20% (which is a "caution" level), if interest rates rise or income is lost, that ratio changes very quickly. This is the same in Finland of course, but it feels like it would be easier to understand in terms of total debt to total income.

The way information is presented affects the way it is understood. For instance, in Europe, fuel efficiency is calculated as Liters per 100 kilometers. But in the US, it is Miles Per Gallon. Tying the ratio to the distance covered as the standard, means that there is a straight line comparison, no matter the type of car and other factors. This makes it easier to estimate costs too. I haven't vetted the article, but for the Americans, this might help.

However, what I am getting at is that how the information like the debt ratio of fuel efficiency are stated, will affect our understanding of what is going on. Similarly, the information when we are spending our money is going to affect us too. Spending cash comes at an immediate cost, watching the money disappear from the wallet. Buying "one-click" online lowers the sense of loss greatly. The information of buying something for $100 and having it in the hand makes us feel like we got something for our money, but spending $100 on an investment that will be worth $200 in 7 years (10% per year) doesn't give that same feeling.

This is all just information that we get from our actions, feedback and return on our behaviors. What is consistently happening is that the barriers to spending keep coming down, so we spend more. We don't mind this, because it offers us convenience and since we are made to buy "easy", we will do so. It is like buying a "7-minute ab workout machine" from a TV shopping channel to get washboard abs - as convenient as it is, it isn't going to work and at the end of the day, it will just cost us the money we spent on it, a feeling of failure to get results, and space in our basement.

Convenience is good when it add value to our lives, but we have to be careful in how we evaluate what is value-adding. Saving time is good, but what are we going to do with the time saved, and what is the cost we are willing to pay? Paying $1000 dollars a year to save an hour a week might be worth it for some who can monetize that hour or use that hour effectively, but very expensive for someone else who will use that same hour saved to watch Netflix.

But as you can probably see, there are a lot of complexities when it comes to how we value our lives, and a lot of ambiguities when it comes to the costs. The more indirect and hidden the costs become, combined with the more visible the convenience, the more likely we are going to spend our resources, because we can't easily calculate the profit and loss of a purchase.

Behavioral economists spend their time working out how we are affected by different kinds of conditions, and how we are going to act based on them. They know us far better than we know ourselves and they are being employed across every field and industry of the profit-seeking world, as well as in non-profits. Each government and company are trying to influence us into parting with our resources in some way, and the most effective is when we hand over our decision-making powers to them, so they can make the decision on how we spend our money.

Subscription services are a good example of this. And so is tax.

I might be a dinosaur, but I think I see the meteorite approaching.

Taraz

[ Gen1: Hive ]

Posted Using InLeo Alpha