In a previous article I took a look at the Sinopedia series, China Intercontinental Press's 12 part collection of textbook/documentary/propaganda volumes, and I broke the series into 4 sets.

Set 1: Enlightening - These insightful volumes actually managed to hold my attention and made me want to continue reading the series.

Set 2: Useful - Though not exactly gripping, these books were useful enough that I have referred back to them and cited them several times.

Set 3: Semi-useful - I didn't get much out of these except useful data and statistics, but for a China-watcher they're good for that much.

Set 4: Absolute rubbish - Unmasked, unapologetic heaps of Chinese State-sponsored propaganda, and they didn't even have the decency to make their propaganda convincing.

The former review looked at Set 1, the "enlightening" volumes. Here, I want to take a look at set 2, which I labelled "useful." This set consists of China's Ethnic Groups and Religions by Zheng Qian,China's Laws by Pan Guoping & Ma Limin, and China's Political system by Yin Zhongqing. Taken together, these three volumes are an informative (albeit tastelessly propaganda-laden) discourse on, eh, let's say "Civics with Chinese Characteristics."

China's Ethnic Groups and Religions

Despite spiking every page with a prescription-strength dose of Chinese propaganda (the very first page mentions the, and I quote, "Invincible and Victorious People's Liberation Army's" march onto A-Wa Mountain, which was never even a part of China until 1950, when the PLA annexed it on the dubious basis of the Manchurian Empire's never-before-recognized claim of suzerainty over the Wa States (N Ganesan, 269)), this book is nonetheless a fascinating and comparatively exhaustive look at the various ethnic minorities in China, though it tends to shy away from going in depth about religious representation (despite the title, the topic only gets a cursory examination in one chapter). Furthermore, it gives an explanation of just what criteria the Chinese regime uses to determine whether a given group qualifies as a separate "Ethnic Group" or not.

China's ethnic identification incorporated the actual conditions of its ethnic minorities, and apart from Stalin's definition, "Ethnic willingness," "historical basis" and "proximity identification" became three important principles. -P. 24.

Unfortunately, the book rarely goes more than a page without contradicting itself. For example, no sooner does it describe this "ethnic willingness" as a declaration that an ethnic identification cannot be imposed upon an ethnic minority from outside its own ranks, than it casually describes how China did precisely that.

Over 3 million people in Yunnan Province spoke the Yi language but used tens of different names for their ethnicity. They were, however, all identified as branches of the Yi minority rather than a separate one, based on the fact that they all shared common linguistic characteristics and, of course, common cultural traditions. -p. 25

First of all, this is a flat contradiction of the statement on page 24. Second, it's clumsy. Do they "speak the same language," or merely "share common linguistic characteristics?" Those to are not even close to the same thing. If it is the latter, then this ham-fisted criterion would have treated nearly all of Europe as being of the same ethnic group for having similar cultural traditions (most of Europe celebrates Christian holidays) and a common linguistic origin (the Roman alphabet).

Of course, as with virtually anything written on the orders of the Party, Han Jingoism drips from virtually every page.

Many Han people moved to border barbarian [non-Han] areas due to factors such as wars, natural disasters and military settlements. -p. 35

There needs to be a core that plays a uniting role. The Han ethnic group is one of many basic components that has united all components... an ethnic group of higher recognition... Different levels can coexist, even make good use of their own original strengths based on this pattern, and form a unity of multiple languages and cultures. -p.38 (emphasis mine)

In history, China's ethnic minorities generally or significantly lagged behind the Han ethnic group in terms of culture, economy, e cetera. It has long been a common view that ethnic minorities lag behind the Han ethnic group... this viewpoint then begs the question: can ethnic minorities catch up with the Han ethnic group-and when? p. 50

The book also puts its foot in its mouth on page 53 by acknowledging that the death rate among Tibetans in 1953 (before what it has the gall to call the CPC's "democratic reform") was 28 percent. The fact that these deaths almost all happened under PLA guns, somehow escapes mention amid the book's efforts to portray the Han as the "saviors of the primitive, backward non-Han."

And speaking of the way the book bends over backwards to paint Chinese rule in Tibet in a positive light, I deeply question its figures. On page 53 it states that the "overwhelming" majority of the population of Tibet consists of Tibetans and implies that the Han population there is shrinking. Numerous sources dispute this (Asianews; Wong), including this book's sister-volume, China's Political system (p. 10)

The book also goes out of its way to describe the PRC's laws on the preservation of ethnic minorities' cultures, such as the policy of guaranteeing minorities shall receive instruction in their own language (p. 75, 119 & 120). This is useful information for any China-watcher to have, as it shows that their current crackdown on Mongolian culture and language in Chinese-occupied Inner-Mongolia is illegal even by China's Draconian laws (Graceffo).

The book also gives a rather open confession of the Chinese regime's drive to demolish ethnic minorities' historic sites for the sake of economic progress, though they dress it up in the raiment of "[giving] top priority to ethnic autonomous areas when making rational arrangements for resource development projects and infrastructure projects (p. 79)."

But the most shocking thing about the book is that it admits, without a trace of shame or irony, that China's drive to "preserve ethnic minorities' culture" is nothing more than an exploitative song-and-dance... in a very literal sense.

When the 21st century dawned... [the] public begin [sic] to wonder how to convert traditional cultural advantages into economic advantages. p. 110

The implementation of a market economy reveals the value of traditional culture... (p. 110)

First of all, traditional ethnic minority culture with distinctive features is transformed into a priceless tourism resource... Secondly, many cultural activities are developed into products and put into the market. (p. 111 emphasis mine)

What you have there is a repeated and rather disgustingly casual admission that China considers "culture" to be nothing more than odd clothes and rituals that are performed for the amusement of gawking tourists (who pay well to gawk, and of course the money goes mostly to the Han). What's even worse is that the Chinese can plainly see that's what they're doing and they don't care.

For example, as a post-modernist industry, tourism has a deconstructive effect on tourism destinations, decoupling traditional culture from social life, making ethnic culture become more like a souvenir or a commerical venue, and lose its original flavor. This has become a contentious issue.

Of course, this is an issue worldwide. (p. 113, emphasis mine)

"Yeah, it doesn't matter that we're grossly exploiting entire nations that we have subjugated, reducing their centuries of heritage to nothing but party favors, because... you know, other countries have done it to."

I have to re-iterate though, when you cut through the thick coating of Chinese government propaganda (which is actually useful in itself, insofar as it puts the PRC's "Han Savior" complex on rather open display), the book does provide useful information about the number and location of non-Chinese populations living under Han occupation, and gives a thorough (if highly spun) look at how these regions are administered by the Party-State.

And speaking of how China administers things...

China's Laws

This book is useful to read, but not if you're looking for what the title says it contains. There is not a single citation or quotation from a single Chinese law anywhere within its pages. A more accurate title would have been "The Goals and Guidelines of China's Lawmaking Process." It does offer some insight into HOW laws become law in China (though, ironically, it offers less insight into this than its sister-volume, China's Political System, but I digress).

Much like the work mentioned above though, it is useful primarily as an indictment against the regime's own actions. For instance:

The Constitution and the law guarantee freedom of speech, press, assembly, association, procession, and demonstration. (p. 44)

...Just to clarify, I didn't forget to mention a change of venue here. We are, still, talking about China, and a Chinese-government-funded publication just put that into print. And if you're looking around to see if you've just stepped into a previously unreleased episode of Sliders, you're not alone.

If that's so, then the arrests of Xu Zhangrun (Aljazeera Staff), Gui Minhai (Feng), and Joshua Wong (Leung, Smith & Mintz) were unconstitutional even by China's notoriously heavy-handed constitution, hm?

And speaking of alternate-universe-worthy statements, the later pages contain a few other whoppers. For instance:

China's legislation on intellectual property rights... seem [sic] to take its place in the front rank of the world. (p. 101)

...In the highly unlikely event that I have a reader so ill-informed that this requires a response, here it is. For everyone else, let's move on.

One of the oddest things about the book is the way it repeatedly cites the number of laws China has passed on any given topic, as though that is some kind of achievement. Never once (again I say, "never, once") in the 156 pages of the book's main body, does it cite a single concrete example that any of these laws has achieved its goal, or even that the government has taken any steps to check on their effectiveness. The attitude appears to be "there. We, your illustrious and beneficent ruling Party, have produced a piece of paper with a funky red stamp on it. We've done our duty. Be grateful, peasants!" I will confess, however, that this in itself is a telling commentary on China's mindset: it doesn't matter what the results were. All that matters was we made a show of doing something. Success or failure should not matter as much as the symbolic message we sent by the appearance of action.

The one undeniably useful bit of this book is Appendix I (and by the way, I don't know why the Roman numeral is there, considering there is only one appendix), which contains a complete list of every national law passed by China's National People's Congress since the enactment of the current constitution (in 1982). Admittedly, it does not offer any information about any of these laws except their names, but that information can be found elsewhere. Then again, considering that China's laws are quite selectively enforced in China, so there is a limit to how true that statement can be said to be.

China's Political System

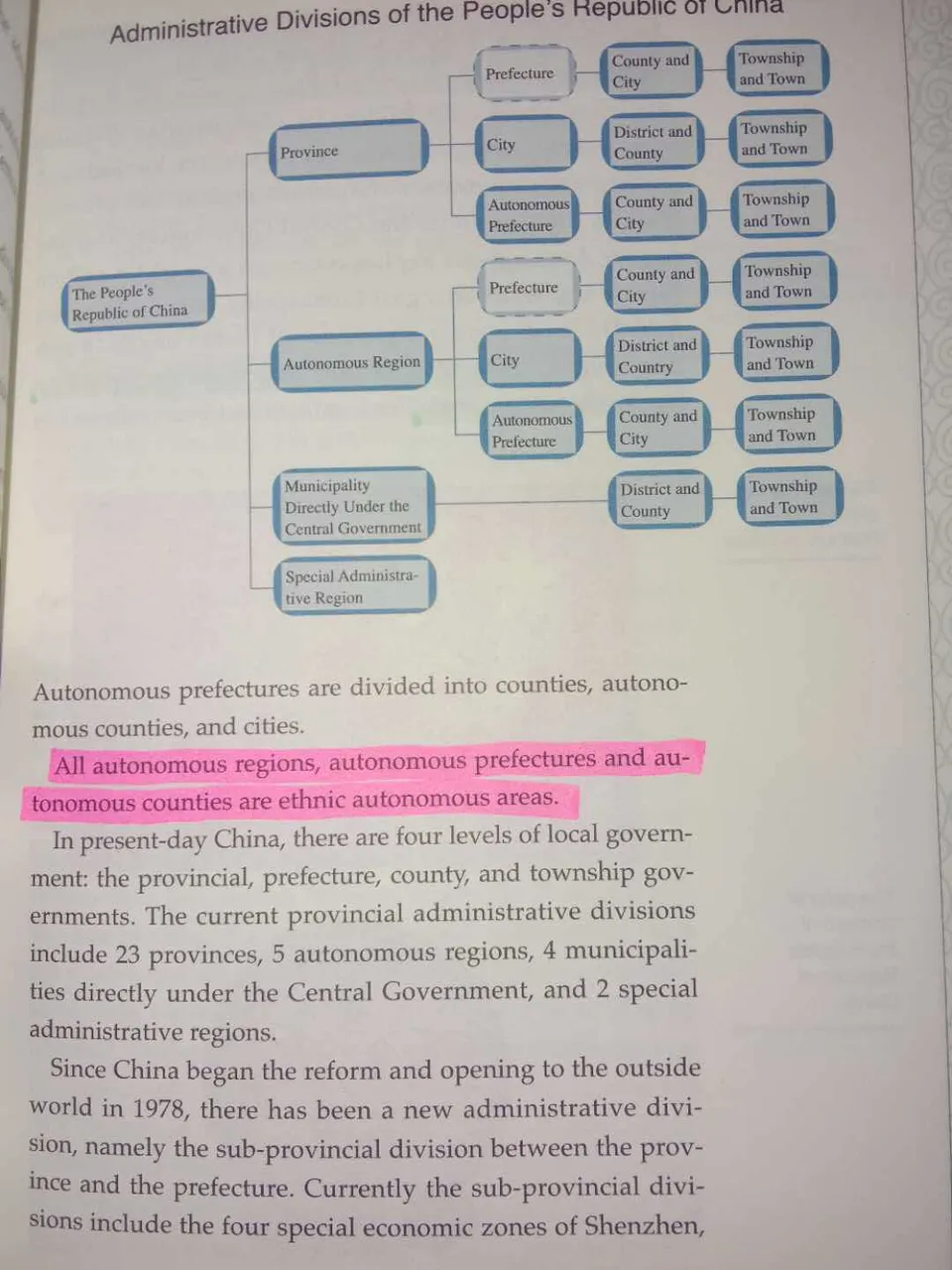

This is, in my opinion, the most practical book of the series. The propaganda is kept to a dull roar (with the exception of endless repetitions of the phrase "all power belongs to the people"), and frankly, it's a clear, easy-to-understand analog to one of America's high school Civics textbooks. On page 5 there is a top-down chart showing China's divisional structure (it's interesting to note that "city" and "town" are not different sizes of the same classification under China's structure but rather, towns are parts of cities, and the term "city" basically equals what the US would call a "Greater Metropolitan Area").

As to why I highlighted the selected line, refer back to China's Ethnic Groups and Religions for more details about what constitutes an "ethnic autonomous area." This is a handy chart for a China-watcher to have on-hand though. Notice that a "city" appears at multiple tiers on the chart, right?

Well, this is based on the size of the city. When you hear something referred to as a "prefecture-level city," that means a city with a large enough population to be governed as its own prefecture (third tier up), and broken into districts which are themselves as large as some cities (example, Beijing). A "county-level city" is a city city that is part of a prefecture, and is broken into townships (example, Zhongshan). A "township" is a municipal entity with its own mayor and its own power to enact.. well, they don't call them "laws" at anything lower than the national level (see China's Laws p. 20), but to enact policies that only apply within its own limits, yet which is not large enough to be called a city.

I've explained this by way of an example of what the book primarily contains: charts and explanations of what the PRC's actual political structure is. It contains explanations of China's electoral process. Yes, at local levels they do actually have one. Admittedly, candidates have to be approved by the Party and the Party decides whether or not to accept election results so it's mostly symbolic, but they do have one.

Also, the book explains how officials elected at lower levels by the populace will, themselves, vote on higher representatives, who will in turn vote on national representatives, who will in turn elect members of the Politburo, who will in turn elect members of the Politburo Standing Committee and, of course, the Chairman.

I'm not going to blow smoke up anyone's ass by trying to pretend that this in any way equates to a "People's Government," but the explanation of China's government structures found within this volume are among the least propagandized and most no-nonsense part of the entire series.

So Who Should Read Them?

Essentially, if you are a China-watcher, you should read them. If not, then there is little to be gained from them, as none of them touches on any aspect of China's external workings, but for those who want to be able to comment on the internal affairs of China with anything passing for knowledge, these provide valuable insight. They're especially useful inasmuch as very few of the PRC's own citizens have ever bothered to understand how their government functions (unlike the US, they're not taught this in school), and when some wumao hits the "laugh" button on one of your social media posts and tries to say "you stoopeeda Wes-ta-na! You kno na-ting abou-ta Chah-na," there's a delightful satisfaction that comes from being able to call him out with cited and sourced data from his own government that proves you know more about China than he does, in fact.

And of course, knowing what rules China sets for itself is useful for China critics because there's little to be gained from railing against the Party's actions because they don't fall in line with Western laws. But to be able to point out, in writing, that the Party can't even be trusted to follow it's own laws, is useful when for any "soldier" in a "public opinion war."

Works Cited

Aljazeera Staff. "China Arrests Law Professor who Criticised Xi Over Coronavirus." Al Jazeera. 6 Jul, 2020. Web. 26 Sep, 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/07/06/china-arrests-law-professor-who-criticised-xi-over-coronavirus/

Asiatimes Staff. "Beijing Sends a New Flood of Han Migrants to Lhasa: Tibetans Risk Disappearing." Asiatimes. 24 July, 2010. Web. http://www.asianews.it/news-en/Beijing-sends-a-new-flood-of-Han-migrants-to-Lhasa:-Tibetans-risk-disappearing-33294.html

Feng, Emily. "Hong Kong Bookseller Sentenced By China To 10 Years For Passing 'Intelligence'" NPR. 25 Feb, 2020. Web. 26 Sep, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/02/25/809163417/hong-kong-bookseller-sentenced-by-china-to-10-years-for-passing-intelligence

Graceffo, Antonio. "China’s Crackdown on Mongolian Culture." The Diplomat. 4 Sep, 2020. Web. 26 Sep, 2020. https://thediplomat.com/2020/09/chinas-crackdown-on-mongolian-culture/

Leung, Jasmine; Smith, Nicola & Mints, Luke. "Hong Kong Activist Joshua Wong Arrested for 2019 'Unlawful Assembly'." Telegraph. 24 Sep, 2020. Web. 26 Sep, 2020. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/09/24/hong-kong-activist-joshua-wong-arrested-2019-unlawful-assembly/

N. Ganesan & Kyaw Yin Hlaing eds. Myanmar: State, Society and Ethnicity. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, February 1, 2007.

ISBN 978-9812304346

as

Pan Guoping & Ma Limin. Trans. Chang Guojie. China's Laws. Beijing, 2010. China Intercontinental Press.

ISBN 978-5085-1719-3

Wong, Edward. "China’s Money and Migrants Pour Into Tibet." New York Times. 24 July, 2010. Web. 26 Sep, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/25/world/asia/25tibet.html

Yin Zhongqing. Trans. Wang Pingxing. China's Political system. Beijing, 2011. China Intercontinental Press.

ISBN 978-7-5085-1300-3

Zheng Qian. Trans. Hou Xiaocui, Rong Xueqin & Huang Ying. China's Ethnic Groups and Religions. Beijing, 2010. China Intercontinental Press.

ISBN 978-7-5085-1685-1