Scientific research gets published into many journals from a variety of fields. There are papers for "hard" or natural sciences[1] that are concerned with the natural world like biology, chemistry, physics and astronomy. These are considered to apply a more "pure" form of the scientific method compared to the "softer" sciences related to social life[2] like psychology, sociology, economics, political science and history.

There are some issues with both of these categories of scientific research. Spin and replicability issues can arise that cast doubt and put results into question. Spin is normally thought of as the domain of news media, politicians and propaganda where biased presentation of information is used to get a certain message accepted. Scientific literature isn't immune to using similar practices.

publicdomainpictures.net/CC0 Public Domain

When it comes to biology and biomedical research there is a high level of distortion that creeps up in research papers. Authors and researchers use certain methods to make the data appear more favorable in order to validate a certain conclusion or result. This leads to misleading the readers of these scientific papers.[3]

'Spin' or 'science hype' is a problem as it "can negatively impact the development of further studies, clinical practice, and health policies".[4] Further research can then be directed into areas that actually lack evidence that merit it, as well as increase financial investments into useless or harmful applications.

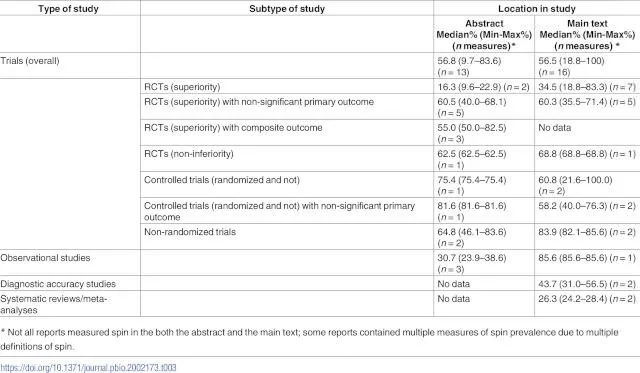

Researchers at University of Sydney Charles Perkins Centre and Faculty of Pharmacy set out to determine how pervasive spin was by conducting a meta-research study of other meta-research studies. They conducted a systemic review of 34 other reviews/reports that had analyzed spin in "clinical trials, observational studies, diagnostic accuracy studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses".[4].

"Half of the reports (17/34, 50%) that assessed spin in published literature assessed spin in both the abstract and main text, 4 of which specifically compared the main text results to the abstract and/or main text conclusions as a measure of discordance. Suggesting that the consequences of spin in the abstract were more severe given that many clinicians rely on abstracts alone, 7 reports (7/34, 21%) assessed spin in the abstract only. Nine reports (9/34, 26%) assessed spin only in the main text of the article. Three reports (3/34, 9%) additionally assessed spin in the articles' titles."[4]

The most prevalence of spin was found in research about non-randomized trials. The meta-research reports (34) had 84% spin tactics used in the main text of the studies looked at, and 65% used in the abstracts alone.

Table 3[4]/Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY)

The studies looked at in the 34 reports showed an average of 30% (141/474 of studies analyzed) in abstracts and 22% (75/346 of studies analyzed) in main text that contained "high" levels of spin in their conclusions. A high level of spin in conclusions is defined by Boutron et al.[6] as:

- "no uncertainty in the framing of conclusions"

- "no recommendations for further trials"

- "no acknowledgment of the statistically nonsignificant primary outcomes"

- "making recommendations to use the intervention in clinical practice"

Spin was most commonly performed through selective reporting of only statistically significant data and distorting "statistically nonsignificant results" like stating something "shows an effect". This can lead to an overemphasis on certain data that overshadows other data or outcomes. There is also the use of causal language to mistakingly attribute causality such as suggesting "X leads to Y", "X increases Y", or "X facilitates the rapid recovery of Y". Tone inferences such as "this study shows that" or "the results demonstrate" is another factor.[5]

When spin is used, researchers can give the impression that claims are supported by the evidence when they aren't exactly. Certain data can be favorably presented or other adverse data can be underreported to produce optimistic abstracts. Clinical practices can be take research finding as recommendations for them to pursue.[3]

Conflicts of interest and funding sources were looked at in 19 of the 35 meta-research studies associated with spin, but no clear conclusions could be drawn from hypothesizing these factors as the source of distortions and spin. It's possible research incentives or rewards contribute to the construction of positive conclusions in order to gain media attention or to be accepted for publishing.[3].

Lead author, Kellia Chiu, said "[t]he scientific academic community would benefit from the development of tools that help us effectively identify spin and ensure accurate and impartial portrayal and interpretation of results."

In addition to initial research that is presented through spin or hype, even if the research is without these influence, there is also a problem of being able to replicate findings. A 2015 study[8] tried to revalidate the proposed cause and effect of some research by reproducing 100 experiments. The alleged "statistically significant" effects found in 2/3 of the original studies could not be replicated.

It was done on psychological studies, but other fields of research like cancer studies also fail this basic check of replicability. There are incentives to publish research which shows a causal link ("X leads to Y", "X has an effect on Y"). This biases researches to find effects. when experiments are done, researchers can be motivated to report on favorable effects that prove a hypothesis, and under-report others that would nullify their hypothesis. Data is farmed and cherry-picked to confirm results that are desired. But the finding may not be repeatable, as is often the case. [7]

This behavior of distorting data is often encouraged by those funding the research who usually want a certain result. Sensational findings can get more rewards compared to others which make more modest claims. The media latches onto the hype of certain stories. Researchers are thus encouraged to issue press releases to try to garner more attention and popularity which can lead to more funding. A lot of funding in universities is allocated through a numbers game. The more publications are made, the more funding can tend to be provided, regardless of the content. This encourages simply pumping out papers to be published. [7] Journals are often more interested in publishing papers with positive conclusions which means others that establish negative or inconclusive findings can get pushed to the bottom of a wait list for approval.

One effort to make research more honest is to remove incentives for publishing by accepting to publish research before any experiment is run. The goal is to reduce farming for data and just present it as is, no matter the outcome. Statistical competency is lax in some cases as well. And what makes things worse, is that some researchers don't release the statistical methods and data which means others can't verify what they did exactly, and replication is harder to do. Some publishers and editors don't have a properly defined statistical methodology, and mistakingly access flawed statistical data used to conclude findings. The Open Science Framework is a good way to get data reviewed before publishing one's work and avoid spreading incorrect information.

These might help to some degree in mitigating the replication crisis, but the real solution is for scientists to change their mindsets. This would require admitting that a conclusion can be true or false, not blindly standing their ground and trying to force it to be what they want it to be. Curiosity, uncertainty and doubt are a scientists friend.

pixabay/CC0 Creative Commons

When publishers don't know how to detect flawed science, this can result in hoaxes getting published. Or when it's a pseudo-journal, people can accept a study without knowing they are bing fooled. Take the case of Gary Lewis from Royal Holloway, University of London. He announced on his Twitter account that he "submitted a hoax manuscript to a predatory journal. The finding? Politicians from the right wipe their ass with their left hand (and vice versa) - big breakthrough! Manuscript accepted w/o review".

His intentional-hoax paper concludes the following:

"The descriptive statistics showed a clear pattern. Politicians of the right were more likely to wipe their bottoms with their left hand (4 out of 4). The opposite pattern was seen for politicians of the left, with 3 of 4 wiping their bottoms with the right hand (Jeremiah Doorbin responded that he used a munchkin from The Sound of Music to do the wiping, but intimated that if did the wiping it would depend on which hand was free at the time). Using structural equation modeling us formally confirmed this finding – the AIC was 1654.23 and the RMSEA was .02. These are excellent fit statistics although the model makes little sense."[9]

Notice the part about a munchkin from the Sound of Music. The flagrant ridiculousness and falseness of this "study" is obvious, and there have been others like The Conceptual Penis, but some "studies" aren't so obvious. Different studies can contradict each other, purporting different conclusions, so they can't both be true. Yet they are published as science or "truth". At least that's how it's played out in the media and how most people take it when the media says it's so. And some studies snowball one after the other for years, only later to be proven to be false, sometimes uncovering dubious funding sources that pushed for false conclusions to be drawn.

Sometimes even when there isn't spin used, it can still be hyped up by the media who don't read a study properly and come to the wrong conclusion themselves. The hype of a publication can still be spread despite all efforts made by a researcher to present the data honestly. It would be great if the problems of replication were resolved so that studies could more easily be verified and bad science could be stopped before moving ahead with further funding or wasted resources.

If researchers stopped using spin to hype up their findings, that would also improve the reliability of scientific papers. Despite science not being able to control media, scientists can take it upon themselves to be more vigilant within their field and apply better standards as individuals and as a collective workings towards the honest discovery of what 'is' in reality.

With these potential misrepresentations of the data, it doesn't mean the conclusions are necessarily wrong even if worded with distortions. Many -- if not most -- studies are accurate overall. Progress is made through research. If all the studies had false conclusions, nothing would move forward in science.

References:

[1]: Hard and soft science

[2]: Social science

[3]: Watch out for hype—science 'spin' prevalent, researchers warn

[4]: Chiu K, Grundy Q, Bero L (2017) 'Spin' in published biomedical literature: A methodological systematic review. PLoS Biol 15(9). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2002173

[5]: Lazarus C, Haneef R, Ravaud P, Boutron I. Classification and prevalence of spin in abstracts of non-randomized studies evaluating an intervention. BMC Med Res Methodology. 2015;15:85. DOI: 10.1186/s12874-015-0079-x

[6]: Boutron I, Dutton S, Ravaud P, Altman DG. Reporting and interpretation of randomized controlled trials with statistically nonsignificant results for primary outcomes. JAMA. 2010;303(20):2058–64. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2010.651

[7]: The Replication Crisis in Science

[8]: Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 28 Aug 2015, Vol. 349, Issue 6251: DOI: 10.1126/science.aac4716

[9]: Gerry Jay Loui. Testing Inter-hemispheric Social Priming Theory in a Sample of Professional Politicians-A Brief Report. Psychology and Psychotherapy. June 15, 2018.

Thank you for your time and attention. Peace.

If you appreciate and value the content, please consider: Upvoting, Sharing or Reblogging below.

me for more content to come!

me for more content to come!

My goal is to share knowledge, truth and moral understanding in order to help change the world for the better. If you appreciate and value what I do, please consider supporting me as a Steem Witness by voting for me at the bottom of the Witness page.