The Role Archetypes series is focused on presenting archetypal character roles in a way that focuses on their development throughout stories, with a particular eye to games (although most of the examples given will be taken from literature).

Today we're going to wrap up the Ally, the sixth of ten roles we'll explore.

Derivative Forms

The Ally is somewhat different from other character types because of how they are developed. In the first part of this overview I already mentioned that the Ally can be a manifestation of the Hero's anima or animus, in a psychological sense, but there are a couple other variants that can be deduced; these are not so much entirely different archetypes (as some variants tend to be), but rather different approaches to the Ally archetype.

The Brother-in-Arms

This type of Ally is very similar to the Hero in their perspective. This is the sort of character you'd expect to see in a war film (think "Saving Private Ryan"). These Allies differ from the Hero primarily in terms of their capabilities; the Hero comes up with a novel breakthrough or completes a feat, often a sacrificial one, which denotes them as special from the others who share their lot.

This has a key psychological element, namely it tamps down on the revolutionary effect that the Hero frequently has (or, in the case of a Hero whose role in the cultural psyche is to be revolutionary, actually amplifies it). There are downsides to this sort of Ally that a writer should be aware of, primarily stemming from one core issue: a Brother-in-Arms is difficult to differentiate from the Hero.

Because the Brother-in-Arms does not provide alternatives to the Hero, they do a worse job showing the Hero's flaws and humanizing them; this is something that might actually work well in a realistic story, especially if the dramaturgical elements are focused on a psychological element of the Hero: the Hero is otherwise identical to their fellows but has some hidden strength or new revelation that carries them through.

The biopic "American Sniper", a portrayal of the life of Chris Kyle, presents some of the issues that can come up with this sort of Ally; Chris Kyle as a heroic individual is primarily anchored to his wife and a variety of Brother-in-Arms figures; this provides a sort of binary conflict between a desire for peace and a desire to protect the peaceful world of home.

When done well (as "American Sniper" is generally considered to be), this is an opportunity to show a psychological transformation; but when done poorly it can lead to a flat story, or one which misses the point which it originally attempts to make.

The Alternative

The Alternative is another example of an Ally variant. They are the second-in-line to the Hero's role, as it were. They often will have many of the same merits, but a different approach and methodology. It's worth noting that to fulfill this role there must be some reconciliation or at least grudging acceptance of both parties; if the Alternative winds up siding against the Hero they may be a Shapeshifter.

In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, this is represented by Iron Man and Captain America. It is also represented by similar "polar opposite" match-ups; Frodo as a Hero is complemented by Aragorn as the Alternative.

The reason for the Alternative to exist is that it shows the possibility for multiple acceptable beliefs.

In Tolkien's Frodo and Aragorn we see a peculiar reflection of Tolkien's political beliefs:

My political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning the abolition of control not whiskered men with bombs) — or to ‘unconstitutional’ Monarchy.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien

Frodo represents the autonomous and anarchic Shire; there is no official government and even someone who bears the mantle of authority (e.g. Sheriff) within the Shire has no real legal system behind them; they have the title by consent of others and it affords them no special privilege.

This is not to say that there is strictly speaking anarchic political theory behind Tolkien's Frodo character, but in any case Frodo represents a possibility for life without what we would consider a modern state.

Aragorn, on the other hand, is a manifestation of Tolkien's predispositions toward a benevolent monarchy; a perfect righteous king, but one who cannot bring about the paradise that the Shire's self-organization brings. He is not the Hero of the story, but he represents another alternative way of life which can be almost as good (or, perhaps, equally as good as the Shire, but for people who have different needs).

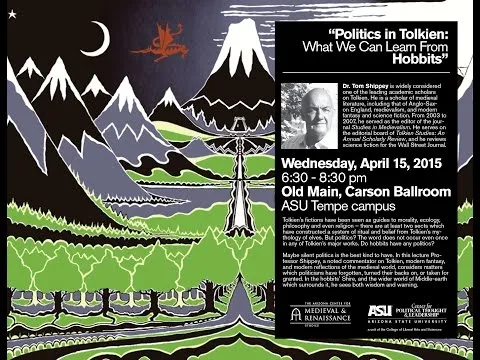

For more on the political implications of the Shire, check out this lecture by Tom Shippey (I was in the audience, though I'm not on camera at any point).

Video courtesy of ACMRS Arizona

The Protégé

The Protégé is an Ally who takes on a sort of subordinate role to the Hero. As a potential successor to the Hero, they follow in their footsteps while not presenting as much of an alternative perspective. Classic examples are often found in the children of a Hero (e.g. Telemachus in The Odyssey).

The Protégé is used when it is important to emphasize the role that the Hero will play in transforming their world; they may also embark on a partial Hero's Journey, though they are not yet ready for it and will require the Hero's assistance to fulfill their full purpose.

From a psychological perspective, this sort of figure has an interesting role, and must often be explored in a case-by-case basis. However, the Protégé being successful is often a statement of a sort of statement of (or as a manifestation of anxiety about) the Hero figure's long-lasting and persistent effects in the universe.

Application to Games

The Ally may actually be one of the hardest archetypes to get right. A lot of games will feature a sidekick or sections where a player takes on the perspective of a different character from the main Hero, but these characters often feature only tangentially in the main plot and can actually be disadvantageous to the experience and narrative.

The fundamental difficulty comes from figuring out ways to include an Ally that are useful and do not detract from the plot, but also keep enough of a focus on the Ally to let them be significant in storytelling. A lot of games can do this well for a short period of time (I think of the Fallout series' dedicated character questlines), but it's more difficult to do this when the Hero is engaged in the Hero's Journey.

The dynamic between Talion and Celebrimbor in Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor and its sequel is an example of how this can be done well, as are the dynamics between Lara Croft and her companions in the 2013 Tomb Raider reboot. However, it's worth noting that if a character's role is largely mechanical, rather than narrative, the effect can be lost: the Far Cry games have been struggling with this and haven't quite managed to create a character who serves in a satisfying role as the Ally, though many of the accompanying characters are still interesting and vibrant parts of the game universe despite their limited narrative application.

Wrapping Up

The Ally is complicated and plays a deep role in the story; they help to illuminate the depths of the Hero, and the variant of Ally (if the Ally is not a more traditional example) can often play a role in expressing a sort of zeitgeist; they manifest the concerns or needs of the writer's psychic situation.

Navigation

Navigation

Introduction and Overview

Previous Entry: Ally Part 1: Overview and Examples

Next Entry: Villain Part 1: Overview and Examples