He could see they were dragging a dog. A rope was tied around its belly and its head flopped limply against the ground. There were five of them, the oldest maybe ten or eleven. It was hard to tell exactly because they were bundled up in winter clothing. They traveled in size order, the smallest trailing behind with legs that looked as though they were having trouble negotiating the tangled underbrush of the forest.

They hadn’t spotted him, probably because he was crouched behind the reeds and because they were apparently preoccupied with transporting their cargo.

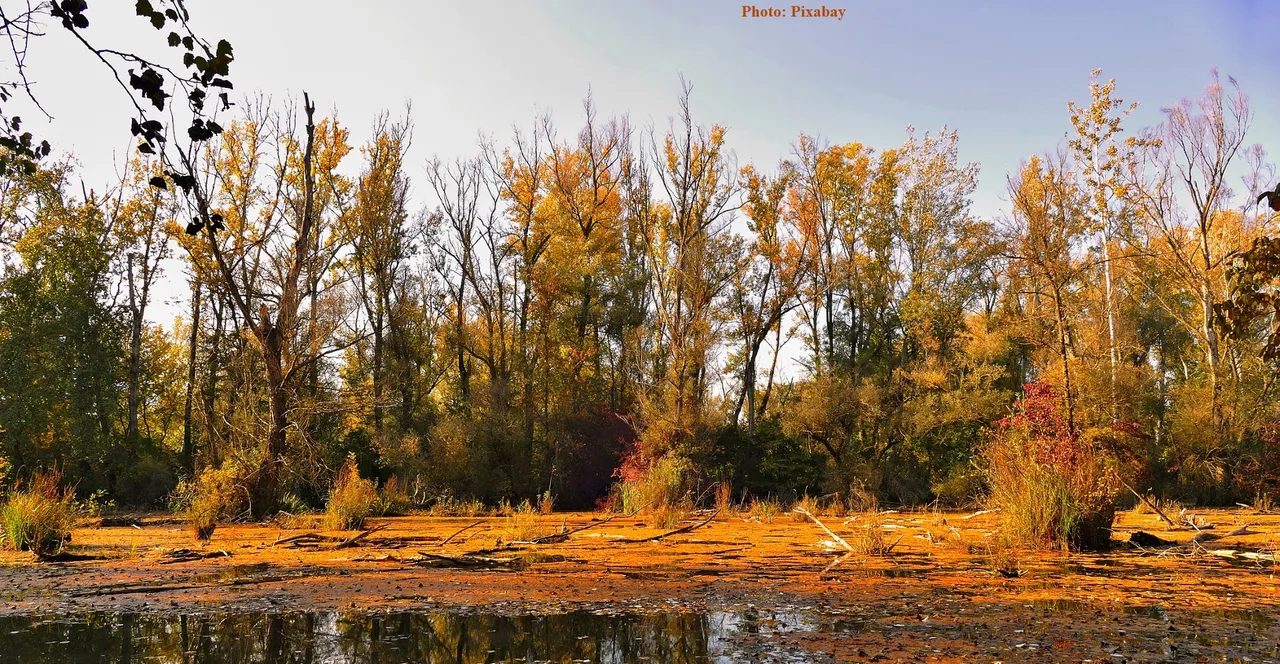

Donald had been at the periphery of the swamp for most of the afternoon. The area was a minefield of venomous snakes. So far he'd managed to bag one large cottonmouth and the remains of a small copperhead for the herpetology lab at the State University. He didn’t find the process of collecting stressful. It was a welcome relief from personal issues that had absorbed him for the last few months. Venomous snake collection required an extraordinary degree of concentration. There was no room for extraneous speculation.

But the children brought him away from the snakes. The youngest one looked just like his daughter had, when he first put a snowsuit on her. She had the same kind of waddling, uncertain gate.

He watched them as they walked purposefully to the side of the mudhole, stopped, and let their rope fall to the ground. There were two boys and three girls. The boys were obviously in charge. They were the ones who were dragging the dog. All of the children wore caps, with side flaps drawn tightly over their ears. The girls were dressed in a hodgepodge of outer garments, apparently arranged more for warmth than cosmetic effect, and both boys were wearing men’s outfits, rolled at the ankles and wrists to keep hanging parts out of the way. When they stopped, the boys rubbed their palms, as though the rope had chafed their skin.

After a time the larger boy picked up the rope and started pulling again, around the side of the mudhole toward Donald. The girls didn’t follow and the smaller boy trailed behind. As the boys drew closer, Donald heard them making a plan.

“We’re going to have to get as far in as we can before we throw her. If she doesn’t land in the middle she’s not going to sink.”

Donald was familiar with this swamp. He’d been here before and he knew that the mudhole the kids were planning to utilize for a burial ground was actually a huge sinkhole. Anything that landed in that mud was going to be swallowed up in very short order. It’s why the surface was so clear--the mudhole acted like an enormous garbage disposal.

The boys turned about a yard from where Donald sat and walked a couple of inches into the mud, until the tops of their shoes were covered with black slime. Donald had to act fast. He knew enough about swamps to understand it would be very hard to pull one of these kids out if they started going down.

He stood up, cleared his throat and raised his hand high in a salute. With a cool glance they seemed to size him up right away. Expensive jacket. New (though muddy) boots.

“Hello there.” He walked toward them quickly in an attempt to stop them from going any further into the bog. “I’m from the University, collecting snakes.” That usually earned him respect from anyone under the age of twelve.

They stared at him and didn’t answer his greeting. It wasn’t that they were afraid. They just didn’t seem to be in a hurry to say anything.

“What happened to your dog?”

“She’s dead. Poisoned. We found her in our basement.”

“That’s terrible. How do you know he was poisoned?”

“She. Her name is Hortense. Cause she’s not the first.” The younger boy had an edge to his voice that was missing in the older boy, though he was warming to this line of conversation. “Someone’s been poisoning our dogs. We buried the rest, but Hortense was too big. And the ground is hard now. So we thought we’d bring her up here to be buried.”

Donald could smell her as he got closer. She had been dead for a while, that was for sure. He didn’t know how they could stand the odor. Her belly was distended and the lower half of her mouth was gone. The other half was crawling with maggots, which had also migrated to her left eye socket.

Donald tried to keep the dog out of his field of vision as he talked to the children.

Sensations that he had successfully repressed surged into his consciousness. This was almost too painful. The image of his daughter on the slab in the morgue. He had identified her because his wife couldn’t. That had been the beginning of the distance between them. He was alone with the grief from the beginning. Neither one of them could speak about it, not to each other. Not to strangers. Not to family. But it lay there between them and the longer it did the more separated they became from one another.

He turned his mind back to the children in front of him. “How are you going to get her in?”

The older boy explained their plan. “Me and my brother are going to pick her up and throw her as far as we can. Everything sinks in there. We just have to get her far enough.”

“She looks pretty heavy. Maybe you could use some help. I mean I’m here, I wouldn’t mind.”

The boys turned their backs on Donald and conferred. He heard their voices but he couldn’t make out the words.

“All right.” The older boy delivered the verdict. “You take one end and we’ll take the other. Then we’ll swing her hard back and forth until we have some momentum going.”

“Sure. I’ll get the back legs.” Donald didn’t want to go near her head. He circled round to the other side of the dog and looked at the girls. He nodded at them but they didn’t acknowledge him. They stood in a row, their faces solemn, but other than that unreadable.

The stench was almost more than he could tolerate, but he bent down and grabbed the dog’s thin legs. As distended as her belly was, her legs were bony and so encrusted with dirt that he could barely see the black fur underneath. It was hard to get a grip, but he positioned his hands firmly. The last thing he wanted was for that dog to slip away and go flying in the wrong direction.

“Do you know who did it – poisoned the dog?”

The boys looked at him disdainfully, as if getting his help wasn’t worth having to talk to him.

“Nobody’s going to say they did it. Nobody’s that dumb.” The younger boy glared at him when he muttered these words, with an expression that suggested Donald might be the one person in the world dumb enough to admit such a thing.

Despite their disdain he had to ask, “How far did you come with her?”

The younger boy was done with him. Donald didn’t even merit a look any more. But as the boys bent over the dog, angling to get a good position, the older boy patronized him with a curt reply.

“We live down the bottom of the mountain, not that far.”

Donald thought about the geography of the area. He wondered just how far the kids had to walk before they thought it was “far”.

The boys had hold of the dog’s forelegs by now. He could see they were trying to figure out how to lift her without touching her head. They pulled her straight up, each boy grabbing a skinny limb, and let her neck snap back. Her skull banged against the ground with a bony thud and her one remaining eye stared dolefully from the side of her head. One of the girls made a noise. Donald couldn’t make out who it was or what she said. The younger boy gave her a sidelong glance and warned, “If you can’t keep quiet we’ll test it out by throwing you in first.”

This threat was met with somber silence.

“On your count or mine?” Donald asked, wanting the whole exercise to be over as quickly as possible. It wasn’t just the physical discomfort. He was afraid he was going to break down over that dog carcass and cry.

“We start swinging her until we’ve got her going good, then when I say ‘go’ we let go.” The older boy was taking charge. Both boys had spread their legs and braced themselves for the toss.

“O.K., start swinging.”

The three of them moved her first over toward the mud, then back again to the grass. They got a rhythm going and synchronized their movements as though they had rehearsed many times. The dog was heavy and the weight of her almost pulled them along. Donald realized there was an element of danger in this for him too. No matter how seasoned these kids might be as woodsmen, he doubted they had the ability to extricate a grown man from the mud hole.

It reached the point where Donald felt they were ready, but the boys didn’t give any sign so they kept swinging. Finally, as the dog came down low to the ground the older boy yelled, “Get ready, go!”

She went off perfectly, soared across the black mud and landed with a hollow splash. It took a few minutes before there was any sign she was sinking. Everybody watched silently, though Donald thought he heard one of the girls whimpering.

Eventually the mud worked its way around the edges of the dog’s body. Black on black, he almost couldn’t tell. But her weight made it go faster. The girls had moved. Donald hadn’t noticed, but they’d come next to the boys. The children sat down together and stared at their disappearing dog.

“Are you children going to stay here?”

“That’s our dog and we’re staying with her till she’s gone.” They didn’t have any use for him now. He was an interloper and what they were doing was private.

He assumed they would be safe, as safe as they usually were. It obviously wasn’t their first time at the mud hole and the exercise with the dog was completed. He had to get away from death. And the children.

He went back to the log that he had used as a marker earlier in a day. His kit and the sack with the cottonmouth in it were there.

He was done. Even if there had been hours of sunlight left, he would have been incapable of continuing his research.

His feelings hadn’t been so raw since they buried Amber. He could see her face. Not dead, but laughing that day he first put on her snowsuit. He remembered thinking that she was growing so much like his wife.

He thought of his wife. It was as though she had been dead all those months too. As though he lost her. The only thing he’d cared about since they lost Amber were the snakes. And suddenly they didn’t seem very important at all.

The pain was too much alone there, by himself, on the side of the mountain. An unfamiliar longing possessed him. To love. To feel love.

There was a chasm between him and the possibility of affection. He needed to find a bridge over that chasm. He thought he knew where to look. He wasn’t going to spend the weekend at the university, as he had planned. He was going to try to go home. He just hoped that home would still be there for him.

Please note: This story was inspired by an incident that occurred when I was fairly young. Several of our dogs had been poisoned. One of my brothers usually buried our pets, but this time I accompanied him. We didn't meet anyone in the forest, but the dog and the swamp are pretty much as I remember them.

Accent pictures crafted from a Paint 3D program