Now that’s a provocative title for a post! It’s not mine I’m afraid. It’s actually the title of a panel I’ve been invited to speak on this coming Sunday for The Battle of Ideas at The Barbican in London. Title image credit: Pixabay

The Battle of Ideas takes a number of the key political and social issues facing our complexly structured modern society and aims to “… understand today’s turbulence and encourage attendees to grasp this historic moment with hope and optimism” quote source. So obviously, I was delighted (if a little terrified) when one of my colleagues had a schedule clash and recommended me for their panel on public trust in healthcare.

Sunday 14th October, 10:00-11:30: From Anti-Vaxers to Alfie's Army: Have we lost faith in medical science?

In preparation, I thought it’d be a good idea for me to plan out some of the points that I’d like to touch on during the session, most of which are going to come from a (now open access) paper of mine that I’ve not talk about on this blog as of yet 1.

Warning: The post turned out as a bit of a long read

What is Alfie’s Army?

When he was around 7 months old, Alfie Evans developed chronic seizures that led to him falling into a semi-vegetative state. Experts suggested that if he were ever to recover from such a state, Alfie’s lived experience would be equivalent to that of living with a neuro-degenerate disease such as dementia 2.

A selection of headlines related to the Alfie Evans case taken from the following locations*.

A few weeks after the seizures, Alfie’s parents and the hospital had the rare occurrence of disagreeing over his continuing care. His parents wanted to move Alfie to an Italian hospital for a further experimental treatment, while the hospital argued that life support be withdrawn and that Alfie should be left to die. This call was made due to expert judgment deeming that further treatment would prolong Alfie’s suffering and would not be in the child’s best interest 2. The dispute was eventually brought to the UK High Court at which point it became national news.

The moral and legal arguments of a healthcare system overruling the wishes of a parent are likely best discussed by the bioethicists and law scholars rather than by myself in this post (see 3, 4 and 5 for some additional nuance on this issue). From a psychological perspective however, Alfie’s case, and others like it (e.g. that of Charlie Gard in 2017 6), often lead to public discourse that have consequences far outstretching the heart-breaking story at their epicentre, discourse that gets at the very heart of how we now react to emotional narratives in modern western culture.

As in the story of Faye Burdett, from my post on meningitis a few weeks ago, this case of Alfie Evans is another painful occasion where the views on both sides of the disagreement are highly understandable, however, again, its an occasion where everyone is right but, ultimately, no one wins.

Emotional populism

Alfie remained in the hospital for over a year while legal action took place and the courts finally ruled against the Evans family’s final appeal 7.

Throughout this time, the proceedings were reported extensively in the national, and even international, press. As can sadly the case with public interest stories such as this, evidence based debate was often side-lined and replaced by heightened emotive rhetoric, and the conversation was politized into a debate about “socialised health care” that quickly became rife with myths and misconceptions 8.

Supporters of Alfie’s parents gathered under the name Alfie’s Army, with a focal point for discussion and activism being a Facebook group of the same name. Currently the group consists of around three-quarters of a million members.

As the story of the legal battles unfolded, the family would frequently share updates in the form of live-streamed video from inside the hospital, which gave their supporters an unfettered feed of the emotions at the heart of the story.

In the above video, Alfie’s father, Tom Evans, expresses the emotions of a father protecting his child. He genuinely and authentically voices his personal knowledge that his child is in good health and would survive if given a chance (a claim that was refuted at the time by medical professional charged with caring for Alfie).

“Look at my health health son, who is undiagnosed and certainly not dying”

He later goes on to rally those that feel similarly to protest at the hospital:

“If anyone wants to come to Alder Hey [the hospital where Alfie was being cared for] right now, and stand outside, and tell them to release our son. Feel free to quiet protest, don’t stand on Alder Hey grounds, please stand [across the street] or at the park... Look what the worlds coming to”

Following posting this video through the Alfie Army Facebook group a crowd mobilised, ignored Tom’s request for quiet protest, and tried to storm the hospital where Alfie was being cared for 9.

This was followed by a number of in person, phone call and online threats and occurrences of abuse towards the medical staff (and even other patients) at the hospital 10.

Blame for these events cannot be fairly placed on the Evans family, they were acting in good faith when making their appeals. Alfie’s life support was withdrawn in April of 2018, he was made comfortable and died on the 28th. While the decision was in favour of the doctor’s recommendation, this is in no way a win for the healthcare system. Instead this is one of the many cases that has fuelled a backlash against expert judgement and a case that has left a section of the British public that connected with the story with an emotional scar that may easily open again in future engagements with the system.

Trust

Last year I was tasked with finishing up a systematic review that my team had previously started on trust in vaccination.

The aim with this review was to examine how trust was being measured in the social science literature that studied vaccination, and compare such forms of measurement to psychological theories of trust. An outcome of which would be to suggest improvements for the measurement of such a concept.

That was the idea at least. Try to bring a bit more nuance into the concept and get all of us that research the perception of vaccination using psychometric scales based on the same underlying constructs. The full, open access, paper can be found here. I won’t go into the whole thing in this post, but to help understand how the Alfie Evans story can impact society I’ll run you though our theory-of-trust summary.

The basics of a medical trust decision

There are a lot of moving parts when it comes to trust in vaccination, so to keep things simple let’s start with a basic decision to trust any recommended health procedure suggested by a healthcare professional in a face-to-face consultation.

When meeting a healthcare professional there is often a level of information asymmetry. The healthcare professional (often) has objectively more knowledge about a particular heath procedure than the patient. A decision to trust the healthcare professionals’ recommendation therefore allows a patient the benefit of avoiding the hard work of researching the medical procedure and instead condenses all that work into a single judgement of whether the healthcare professional can be trusted 11.

For this to be a trust judgement there needs to be a choice between options that the patient can make and stakes riding on such options. No choice and the relationship becomes dependency rather than trust. No stakes and advice would not be sought.

In short, the act of trusting places the patient into a position of vulnerability (i.e. if they were wrong to trust the outcome could be worse) in exchange for a reduction in decision complexity.

Making a trust decision

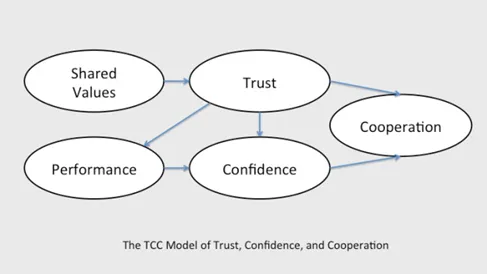

The main theoretical model that I like using when it comes to medical trust decisions is The TCC Model of Trust, Confidence and Cooperation by Earle and Gutscher 12. Without going into much detail, the model suggests that when choosing whether to trust another individual we make two separate judgements: a performance related judgment and a shared values related judgement.

If, for example, it’s a healthcare professional we’re choosing whether to trust, we judge them on how capable we think they are at their job (performance) but we also judge them on whether we think they have our best interests at heart (shared values).

A deficit in either of these judgments may make us less likely to trust, however, a deficit in shared values will always trump a similar magnitude of deficit in performance. For instance, it doesn’t matter how highly competent your doctor is, if what they want is for you to be out of the picture so that they can seduce your partner (in fact, their competency in this case could mean your demise).

The interactions in a medical trust decision

In reality, the healthcare professional is not the sole arbitrator of health knowledge. They work within a health system, and it’s the system that makes a recommendation based on a synthesis of the medical research. Which in turn is then mixed with the healthcare professionals’ expertise and clinical judgement to give a recommendation.

A health system is fallible and slow to adapt to new information, however, as it currently stands, this slow and fallible health system is the only reliable means of turning the gargantuan amount of available medical research into actions that can be implemented to improve an individual’s health. Side note: Although this could be set to change as artificial intelligence continues to progresses, but that’s a blog post for another day.

With this in mind, trust in a healthcare professional and their recommendation can be seen as being nested within a trust judgment made in regards to the healthcare system in its entirety. This nesting may even extend wider to the government, scientific institutes and business that supply and inform the healthcare system.

Trust in vaccination

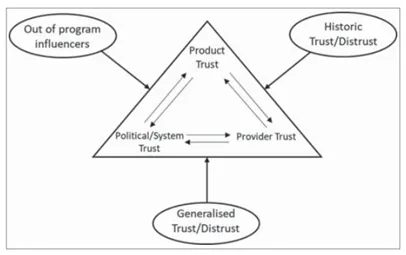

All of the above theory brought us to develop the below visualisation of trust in vaccination.

Here we suggest that the public make three separate but highly interrelated trust judgements. Each of which involve a performance and a values component.

Trust in the healthcare professional that is offering the vaccination

Trust in the health care system as a whole

Trust the science and manufacturing of the product of vaccination itself

Acting on this trust are three external drivers of trust:

Generalised trust:- The willingness to trust other members of society in general (rather than in healthcare specifically). Often measured with the question “do you believe that most people can be trusted?” Part of the concept of social capital for any sociologists out there. The book Bowling Alone covers this topic really well.

Historical influences on trust:- Both perception of performance and shared values are reliant on experience, this means that time is involved. In some cases, perceptions can be passed from generations to generations. The Tuskegee syphilis experiments (and other such atrocities) cast long shadow on trust in the healthcare system 13. For some populations it is sadly all to logical and rational to distrust anything the health system has to offer based on past treatment.

Out-of-program influences:- All non-official sources of health information that also influence decision making. This can include friend and family members, and non-official medical advice from religious organizations, alternative health networks, politicians and celebrities.

We see vaccine-related trust as a complex interaction between the core elements of trust and these external drivers of trust. Trust in vaccination is strengthened when external levers align with the vaccine factors, and weakened when these misalign.

How the anti-vaccination movement and Alfies Army can make us lose faith (trust) in medical science?

Firstly, the anti-vaccination movement and Alfies Army are not the same in my opinion. Alfies Army was largely a “good-faith” movement and anti-vaccination has substantial “bad-faith” aspects to it 14.

Where they are similar, however, is the degree to which emotional narrative exist at their core.

Our emotions are a huge driver of belief, especially when it comes to risk perception. We often make decisions based on how we feel about risk rather than accurately crunching the probabilities involved 15. In also seems that we often feel and then actively collect information to support such a feeling after the fact, a process known as conformation bias

This has obviously always been the case in modern life, seeing as we are functioning today with the same brains we evolved a couple of million years ago. What has changed recently, however, is that these emotions can now be amplified in a way that just ten years ago they could not.

Web 2.0 (social media, user generated content) has not only allowed us all to create feeds that broadcast our lives, but many platforms also includes algorithms that actively promote emotive personal stories over reliable news content 16, this is what may have happened in the Alfie Evans story 17. Platforms push the content but only because they have learnt it is what we want. That’s a fine model for cat videos but when it comes to politics (and most health stories are politics I’m afraid) it’s unleashed a Pandora’s box 18, where an emotional story will always get more eyeballs that the complicated nuanced reasoning of the healthcare system.

When emotion is tapped into it can quickly turn people tribal, with an identity of “us” being defined in opposition to “them”. In the Alfie Evens case, this tribal (and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the group was called Alfie’s Army) nature of the story painted the healthcare system as heartless villains that didn’t have Alfie’s “best interests at heart”. In the Faye Burdett case (mentioned in one of my previous post), the argument from cost effectiveness made it look like that health system only cared about the price tag and not vulnerable children.

In both of these occasions there is a violation on the “shared values” judgement in regards to the healthcare system as outline in the model above.

I don’t believe we have hit the point where faith has been lost in medical science, however, I do believe that this is the process of how faith can be lost in medical science. If we don’t get a handle on how to talk to the public when an emotional story like this hits next time, trust will be eroded further.

About me:

My name is Richard, I blog under the name of @nonzerosum. I’m a PhD student at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. I write mostly on Public Health, Effective Altruism and The Psychology of Vaccine Hesitancy. If you’d like to read more on these topics in the future follow me here on Steemit or on Twitter @RichClarkePsy.

I'm a proud member of @SteemSTEM and you should be too! Find more information about their fine work here

References:

[1] Larson, H. J., Clarke, R. M. (It’s me!!!), Jarrett, C., Eckersberger, E., Levine, Z., Schulz, W. S., & Paterson, P. (2018). Measuring trust in vaccination: A systematic review. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 1-11.

[2] Vox: What we can learn from the heartbreaking Alfie Evans case — and what we can’t

[3] The BMJ Blog: Alfie Evans: Please, just stop

[4] The BBC: Alfie Evans: When are parents denied the final say?

[5] The Health Care Blog: Alfie Evans and the Medical Ethics of Suffering

[6] The BMJ Blog: Alfie Evans and Charlie Gard—should the law change?

[7] The Guardian: Timeline: key events in the legal battle over Alfie Evans

[8] The University of Surrey department of sociology blog: Alfie’s Army, misinformation and propaganda: The need for critical media literacy in a mediated world

[9] The BMJ: Anger as Alfie’s Army protests outside Alder Hey

[10] The Guardian: Alfie Evans: police issue warning over online abuse of medical staff

[11] Cummings L. The “trust” heuristic: Arguments from authority in public health. Health Commun. 2014;26;29(10):1043–56. doi:10.1080/10410236.2013.831685

[12] Earle, T. C., Siegrist, M., & Gutscher, H. (2010). Trust, risk perception and the TCC model of cooperation. Trust in risk management: Uncertainty and scepticism in the public mind, 1-50.

[13] Gamble, V. N. (1997). Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. American journal of public health, 87(11), 1773-1778.

[14] Wolfe, R. M., & Sharp, L. K. (2002). Anti-vaccinationists past and present. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 325(7361), 430.

[15] Slovic, P., & Peters, E. (2006). Risk perception and affect. Current directions in psychological science, 15(6), 322-325.

[16] The Wall Street Journal: How YouTube Drives People to the Internet’s Darkest Corners

[17] Wired: How Facebook’s fake news fix made the Alfie Evans story go viral

[18] Kata, A. (2010). A postmodern Pandora's box: anti-vaccination misinformation on the Internet. Vaccine, 28(7), 1709-1716.

*Headlines in image were from the following locations: i, ii, iii, iv, v, vi, vii

Update

Did the panel, it looked something like this:

I'm second from the right.