Having already reviewed the more useful half of China Intercontinental Press's "Sinopedia" series, this review will approach the bottom of the barrel. To begin, let me go ahead and recap the 4 subsets into which I divided this 12-volume series.

Set 1: Enlightening - These insightful volumes actually managed to hold my attention and made me want to continue reading the series.

Set 2: Useful - Though not exactly gripping, these books were useful enough that I have referred back to them and cited them several times.

Set 3: Semi-useful - I didn't get much out of these except useful data and statistics, but for a China-watcher they're good for that much.

Set 4: Absolute rubbish - Unmasked, unapologetic heaps of Chinese State-sponsored propaganda, and they didn't even have the decency to make their propaganda convincing.

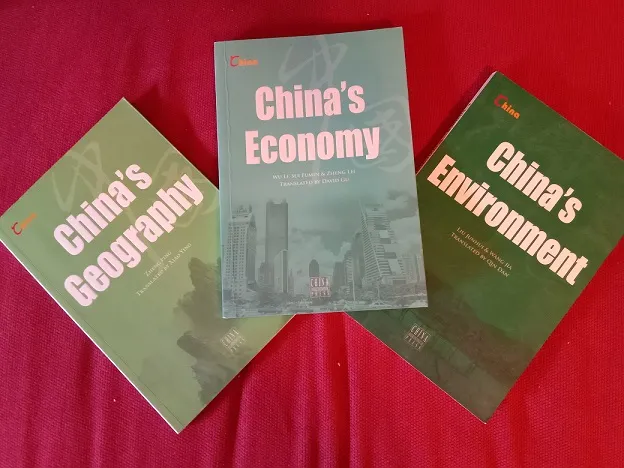

In this review I'm going to examine Set 3, which I labelled "semi-useful." This set consists of China's Economy by Wu Li, Sui Fumin & Zheng Lei, China's Environment by Liu Junhui & Wang Jia., and China's Geography by Zheng Ping. These are the three which are primarily useful as reference sources for China-watchers, mainly as collections of data and maps, rather than books in their own right.

China's Economy

I think at this point I have already established that the preface of each of these books is nothing but self-serving narcissycophantic (1) drivel, so I won't bother debunking the glaringly false assertions of "non-interference" and insistence that all negative press about China is "misunderstood" and "distorted," which fill the first 4 pages. Let it simply suffice to say at this point that anyone reading this series should not punish themselves by trying to digest the preface to any of these 12 volumes. If you start reading on page 5, you find actual information.

To understand China's economy, one must first understand China's economic geography. While setting the conditions and foundation for China's development, China's economic geography also restrains this very development of China's economy. (p. 5)

Ah, okay. So, here we have a reality-based declaration that China's growth is driven by geographical factors, which also hinder it. The admission of this paradox, rather than some mindless declaration of the "inevitable triumph of the Glorious Zhonghua Minzu under the flawless leadership of the Communist Party," like the sort you'd find in Xi's book, is a sign that this section is written by a scholar who has been tasked with writing propaganda, rather than a propagandist who has been ordered to masquerade as a scholar. This is a step up from most of what China's government publishes.

The following three pages are mostly number-crunching. They consist of statistics about the area of China's claimed territory, including land area (notwithstanding the illegality of their presence in a large chunk of that area) and maritime claims (notwithstanding the illegality of those claims). It lists the nations that border China and in what direction, gives the length of China's border and its coastline, names the highest and lowest altitudes in the country, and gives the length of its total rivers as well as its longest river. I suppose these can be useful stats to have all in one place.

But it's the section after that, under the heading "II. Natural Resources," beginning on page 8, which is truly eye-opening.

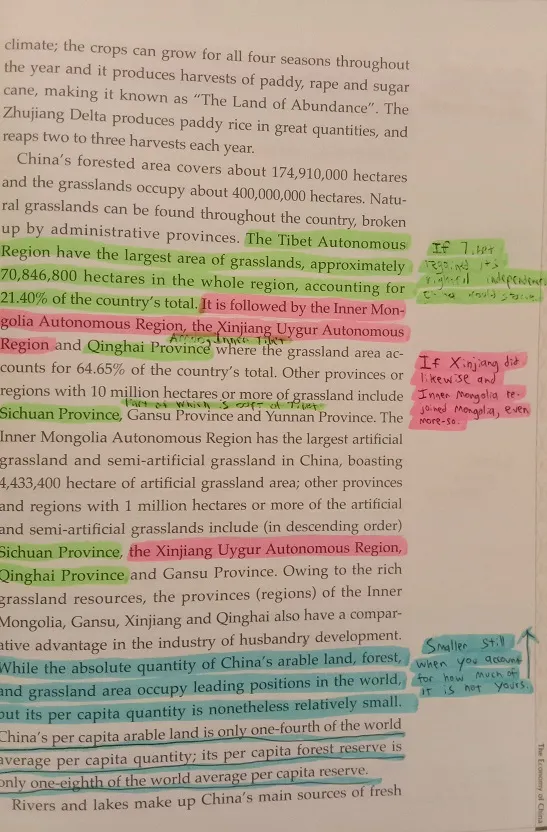

China's forested area covers about 174,910,000 hectares and the grasslands occupy about 400,000,000 hectares. Natural grasslands can be found throughout the country, broken up by administrative provinces. The Tibet Autonomous Region have the largest area of grasslands, approximately 70,846,800 hectares in the whole region, accounting for 21.40% of the country's total. It is followed by the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, the Xinjiang Uygur [Sic] Autonomous Region, and Qinghai [Inner Tibet] Province where the grassland area accounts for 64.65% of the country's total. (p. 9, emphasis added)

Remember in a previous article when I mentioned that the majority of China's arable land is in ethnically non-Chinese border regions and buffer states, all of whom are chafing against PLA occupation, which is a glaring internal weakness the US could exploit if we wanted to shatter China? This is the source I was using.

And of course, the eye-opening information continues.

While the absolute quantity of China's arable land, forest, and grassland occupy leading positions in the world... China's per capita arable land is only one-fourth of the world average per capita quantity. (p. 9, emphasis added)

And again...

The total volume of China's water resources is 2.7127 trillion cubic meters, averaging about 2,000 cubic meters per capita. (p.10)

That figure includes China's claim over most of the West Philippine Sea, a claim which no one except China recognizes. When you remove the WPS from that equation, China's water reserves drop considerably. Also, China's groundwater resources (Fenby 103, Chu 181) and it frames China in a suddenly more vulnerable light, with their capacity to prevent mass death from starvation and thirst hinging upon their ability to maintain a tenuous grip on regions no one in the world recognizes their right to have.

From there, the book goes through a delightful spin on the events of the Mao era (which hits its high point on page 22 with the declaration of having abolished the "landlord economy"). Before softening the dogma with a rather even-handed declaration of why China deemed it in their best interests to be part of the Soviet camp in the early part of the 20th century. Of course, since the authors dare not blaspheme the Communist Faith, they were quick to point out that the reason for the failure of Maoism was the fault not of Mao or of Communism as an ideal, but of the people themselves.

[Some] cooperatives violated the principles of self-willingness and mutual benefits, resulting in the collective economy failing to demonstrate its supposed superiority. (p. 27)

This desperate attempt to save St. Mao of Ze Dungheap from criticism is reinforced on p. 29 by the insistence that the Great Famine of 1959-61 was "natural."

The book continues on in roughly this fashion, alternating between useful statistics (pages 105 - 124 feature an easy-to-follow graph on every page), and useful insight into how China doctors statistics. For example, a side bar on page 32 about the 1981 "Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People's Republic of China" offers a rather calm and unashamed explanation of how China's government rewrote their history of the Culture Revolution, not even bothering to hide that this is what they did.

On page 45 is another admission that "the political incident of 1989," otherwise known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre, is one of several "issues that remain to be solved by the Central Committee." All in all though, the book's primary value is in the statistics it provides, most especially those listed above, which would be vital to any tactician planning the destruction of China.

Quite kind of the Chinese government to publish them. And in English, no less.

China's Environment

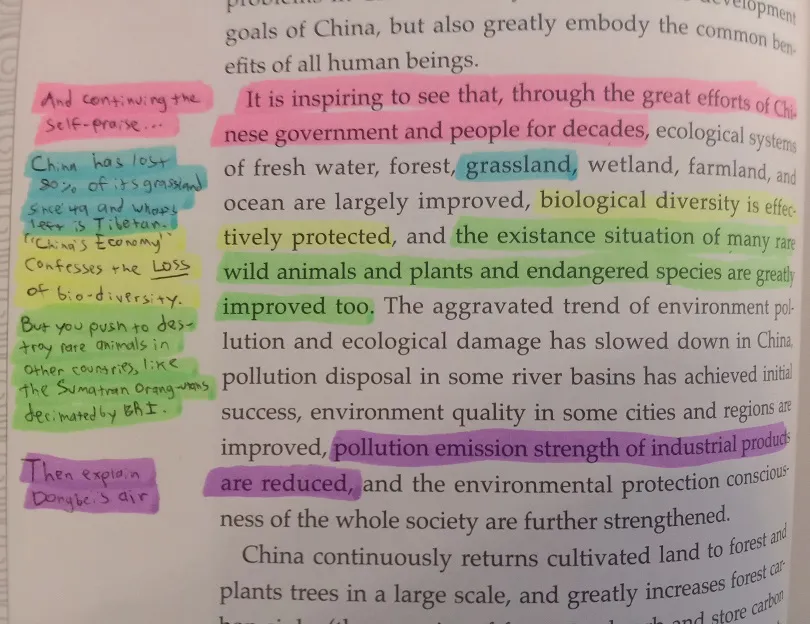

I opened this book fully expecting to read through heaps of self-flattery by the Communist Party, wherein they try desperately to claim China is something other than the world's largest toxic cesspool (as cited before in Fenby and Chu), and I was not disappointed.

As a large responsible developing country, China has always been attaching great importance on [sic] environmental protection and construction... (p. 3)

As economic growth doubles, the environment quality still keeps the level of the early 1980s, and the environment condition in some areas is even improved. (p. 14)

And of course, there is this charming section of page 4.

Pages 20 - 27 are devoted to listing, with much fanfare and pomp, the number of environmental laws China has passed, including the number of government agencies created for the stated purpose of environmental protection. What's missing from this section, much like this series's other installment, China's Laws, is any mention of a tangible result, measurable or otherwise.

And of course, one must chuckle at the phrasing on page 20, wherein the author brags that China "fully carried out public opinion supervision" regarding environmental protection, and "mobilized a number of news media through the country to investigate and report a specific theme each year." If you read carefully, they just confessed that their news is cooked, and that the people are told what their opinions must be. That, though, has nothing to do with the titular issue: China's Environment. It's not until page 33, the beginning of the chapter entitled "Natural Ecosystem," that the book begins to provide anything of substance.

After a quick introduction to China's 5 climate zones (a topic which gets more attention in the sister volume, China's Geography), the author discusses China's freshwater resources.

There are abundant glacier resources in China, including more than 43,000 glaciers, which are distributed in the western part of China and cover a total area of 58,700 sq. km. The glaciers account for half the total number in Asia. Their total water reserves stand at about 5,200 billion cubic meters. These glaciers concentrate in China's western regions. (p. 35)

It is worth noting that these "Chinese" glaciers are ALL, without exception, in occupied Tibet, and that they are the origin of about half of all rivers in Asia. Later on the same page, the author mentions that the Tibetan Plateau holds about half of China's lakes (if "China's" is the right possessive to use for occupied Tibet).

These hints at China's water shortage come to a head on pages 38 and 39 with the admission "Only 6% of the freshwater in the world can be used to support the survival of the Chinese people, who account for 22% of the world population." What follows is a hit-by-hit catalog of different parts of China's water supply that have been found to be among the most toxic and polluted in the world, even by China's admission (pg. 31, 38, 43, 44). This is followed up by data on China's jaw-dropping rate of grassland loss (p. 54).

Later chapters, such as the chapter on biological diversity, offer similarly dismal views of China's environmental situation, despite the chest-beating of the early chapters. For instance, page 80 includes an admission that somewhere between 15% and 20% of all plant and animal species native to China are endangered. The chapter on controlling pollution lists extensive data about the composition of China's air pollutants and the amount of them in the air in various regions, including lists of which cities have the worst acid rain problems.

Page after page, the book's statistics paint a picture of a country that is on the edge of becoming uninhabitable.

China's Geography

The first chapter of this reads like a "who's who" of China's false territorial claims. The chapter entitled "Profile of China's Geography" devotes more text to describing the nations of Tibet, East Turkestan and Taiwan, as well as the Senkakku Islands and the West Philippine Sea, than it does to the entire Chinese mainland. Of course, never content to limit their lies to the present, the Chinese also found a way to shoehorn in a bit of false history with a claim on pages 24 & 25 that the Ming Dynasty tried to limit Han migration into the region known as "Dongbei," consisting of Liaoning, Heilongjiang and Jilin Provinces. The truth is that China had little to do with this. The reason few Han migrated into those region during the Ming Dynasty is because it wasn't part of China then. It was the homeland of the Manchu, the non-Chinese nomads who walked into China through a gate in the Great Wall opened by a turncoat Chinese general, conquered China with ease, and established the "Empire of the Great Qing," which China assuages their egos by pretending was a Chinese Dynasty.

Though, much like the rest of this set, if you can keep your eyes from rolling out of your head long enough to get past the alternate-universe version of history that China loves to peddle, there's useful data. The book breaks China down first into climate zones (of which there are 5), then economic zones (of which there are 3), and gives a detailed examination of the characteristics of each zone. The book also includes a rare glimpse of China's census data (pages 18 & 19). One of the most important aspects of this book, however, is an admission which I wish I'd read in 2012.

On page 70, the author describes the Central Government's decision to make Shanghai a "showpiece," in those exact words, for China's "reform and opening up." This flat, open admission that China's premier city is not by any stretch an indication of normal Chinese life but is in fact the world's largest Potemkin Village, would have changed my outlook on China completely if I had read it during my first trip to Shanghai, when I foolishly fell in love with China.

So Who Should Read Them?

To be brutally frank, for most ordinary people, these are about as useful as an Amish phone book. However, anyone whose interest in China involves crunching numbers will find the stats, charts, maps and data in these three volumes useful, and I certainly hope the Pentagon makes them required reading. Given how easily this information would be useful to anyone making strategic plans against China, it was with some alarm that I discovered the Library of Congress doesn't even have a copy of the first one listed, China's economy. Considering that the LoC's primary purpose is to be the reference library for Congress, this strikes me as a bit of an oversight.

Frankly, if Washington's top brass read these three books in October, China would cease to exist by December.

(1) You will not find this term in a dictionary, and if it is ever added then I expect royalties for having coined it here. It's an amalgamation of the words "narcissistic" and "sycophantic," and its meaning (which should be fairly evident), is "an adjective describing one who praises and flatters oneself in the manner one believes they should be praised and flattered by all others." The closest synonym would be "self-deifying," with a connotation that one is doing so as an example for others.

Works Cited

Chu, Ben. Chinese Whispers. London, 2013. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

ISBN 978-1-7802-2474-9

Fenby, Jonathan. Will China Dominate the 21st Century? Cambridge, 2017. Polity Publishing.

ISBN 978-1-5095-1097-9

Liu Junhui & Wang Jia. Trans. Qin Dan. China's Environment. Beijing, 2010. China Intercontinental Press.

ISBN 978-7-5085-1720-9

Wu Li, Sui Fumin & Zheng Lei. Trans. David Gu. China's Economy. Beijing, 2008. China Intercontinental Press.

ISBN 978-7-5085-1304-1

Zheng Ping. Trans. Xiao Ying. China's Geography. Beijing, 2010. China Intercontinental Press.

ISBN 978-7-5085-1308-9